A crucial initiative started by the charitable organisation I Am Hope, founded by Mike King, Gumboot Friday (4 November 2022) is an annual fundraising drive supporting a free counselling service for children and young adults — a service that is so desperately needed in this country. Read our thought-provoking q&a with Mike King below, and support Gumboot Friday here. Or simply text ‘BOOTS’ to 469 to donate $3 immediately (less than the cost of your morning coffee), with 100% of the money raised today going directly to the cause.

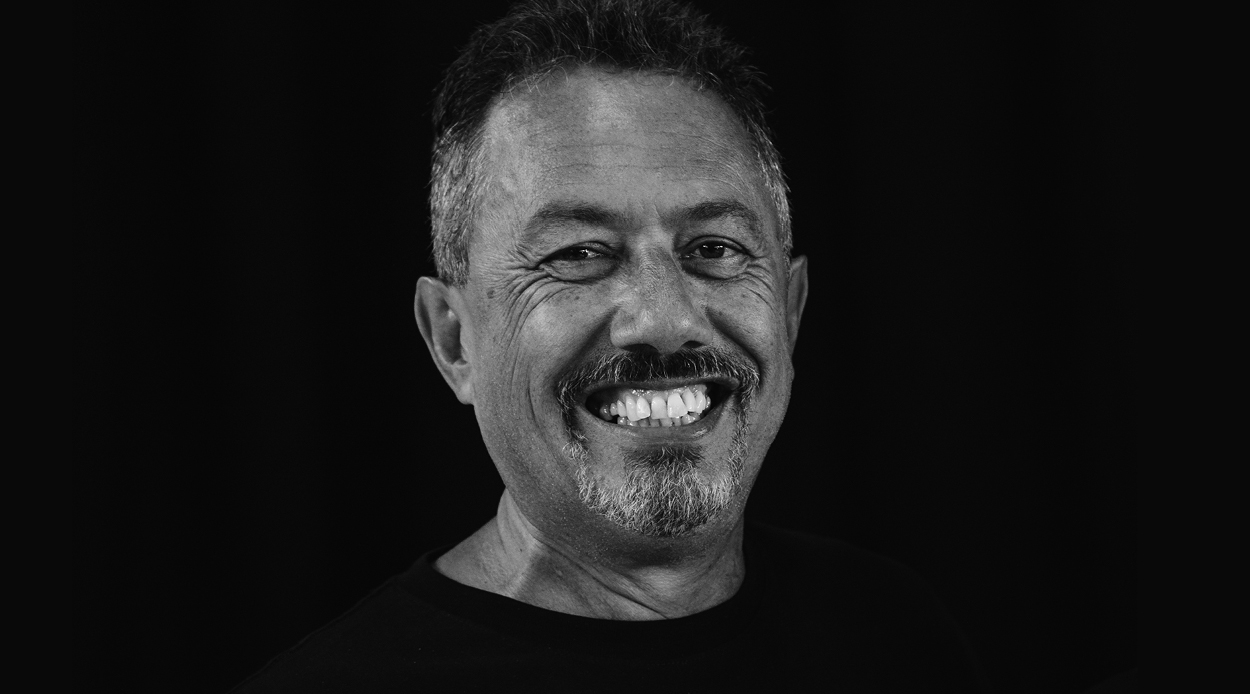

You’d be hard-pressed to find a New Zealander who is fighting as tirelessly for our collective happiness as Mike King. The former comedian, once so prolific he was on three separate shows across multiple channels in the same night, is now a passionate advocate and educator for suicide prevention and mental health. Though he was awarded a New Zealand Order of Merit medal in 2019, he returned it in 2021 as he didn’t feel that enough progress had been made in the mental health sector. Travelling the country, he speaks candidly to young people about his own battles with depression and addiction, breaking the stigma around these topics and helping them feel less alone.

He founded The Key To Life charitable trust in 2012, which encompasses youth and community-focused support group I Am Hope, fundraising appeal Gumboot Friday and multimedia platform The Nutters Club. With Gumboot Friday aiming to raise $5 million to give free counselling to young people, it needs support now more than ever.

Here, King shares an insight into his story, from his journey through comedy to mental health advocacy, to discovering the power of vulnerability.

I grew up in Whenuapai Village. I’d describe myself as a hoha, kid always getting up to mischief. On the outside, I was loud, brash and full of confidence but on the inside, I never felt like I was good enough. Other kids were always better than me. Faster, stronger, academically more gifted, so I was always trying to prove myself, particularly to my dad. I always wanted my dad to look at me like I was a future All Black, pat me on the head in front of his mates and go “yeah, this is my boy”. Sadly my dad was old school — they didn’t pat kids on the head, they booted them in the butt and I got lots of those!

Growing up, we were taught nothing about mental health. It was true-blue, take a concrete pill and harden up! Ironically, my mum was a psychiatric nurse at Oakley Hospital and even she didn’t talk about it.

I’ll never forget my first time on stage. In 1994, I broke my leg and while I was recovering I decided to go and watch some stand-up comedy. Stand-up was in its infancy back then and was more character-based comedy than stand-up. I watched for a couple of weeks until I finally thought “I’m funnier than these guys”, went home and started practising. One week later, I rocked up and asked the guy on the door if I could go on. He said “come back in six weeks when we’ll be holding a rookies night”. “I’m funnier than all your comedians,” I told him. “Here’s $400, put me on and if no one laughs or anyone walks out, I’ll buy the whole bar drinks and you’ll never see me again”. He let me go on.

I smashed it. Unbeknownst to me and the audience, English comedian and writer Ben Elton was watching and he came backstage after. He said to me, “if that’s your first time on stage, you’re going to be famous”. I have never felt so high in all my life. My car got stolen that night and I didn’t care. I think I floated home.

My first TV appearance was a programme called That Comedy Show in 1994. It was terrible. You stand around all day waiting, then shoot the same thing over and over again until, months later, you get to see the very anticlimactic result. The only memory I have of that appearance was all the food I had stuck in my teeth while I was delivering my lines. It taught me the first rule of comedy: always check your teeth before going on camera.

Comedy, like music, is an ever-evolving beast. Tastes change, people change and I’ve changed. Back when I started, political correctness was just coming in and there was a strong fear of change from the macho New Zealand male. That’s who became my audience. I thought the world had gone soft and you should be able to smack kids and make fun of other people’s lifestyles. Over time, I realised I was being a dick and needed to change. Unfortunately, my audience couldn’t accept the change so I moved on.

My comedy experience has been helpful in the mental health and suicide prevention arena. They can be very dark topics, so I use that aspect of my personality to navigate the audience through the ups and downs and break the tension. Comedy also adds stickiness to the message and people are more likely to remember a serious but important message if it is funny rather than tragic.

Billy T. James is, was and will always be the King of New Zealand comedy. Before I became a comedian, I was a chef, and in 1977 I was working in a cabaret in Auckland where Billy T. was our headline act. He would do two shows a night before heading into town for a final show at another club. The man was amazing. On stage, he was a charismatic, lovable rogue who made everybody laugh and feel good without uttering a profanity. That takes skill. Offstage, I would cook him dinner and listen to him and the band tell funny stories about touring the world. These stories became the foundations of his TV shows many years later.

Although I’d never go back to comedy, I do miss touring with other comedians. Andrew Clay (the most underrated comedian in New Zealand) and I did one of the first stand-up comedy tours around the country in 1994. No one knew what stand-up really was back then, so we had to contend with some pretty diverse and strange crowds. In Hawera, they had motorised keg racing going on in the bar while Andy was on stage. Some crowds would laugh, others would boo and some would just sit and stare.

I remember one gig in Whakatane where the audience just sat there for an hour not laughing or clapping — nothing. Andy and I both thought we had died on stage until we said goodnight and the audience stood up, gave us a standing ovation and told us they’d had a great night. We were both like, “yeah, well you could have told ya face”.

Fame can be very alluring for a kid with crippling self-esteem issues — at least that’s how it felt for me. I always thought that if I got famous, all my problems would disappear. Why? Well, if you’re famous that means people like you, and if people like you, it’s natural for a kid to think that you would then love yourself. The cherry on top was, with fame comes money, and I didn’t care what anybody said about money not buying happiness — I was like, “give me the money and I’ll show you happy”.

Getting famous was a million to one shot, so when it finally happened, it was like winning the Lotto. Suddenly I was Mr. Popular with lots of ‘new’ friends, buying happiness wherever I was. Fame became a distraction for the voices of doubt. It was intoxicating and addictive — the more I got, the more I needed. Then one day, I woke up surrounded by material possessions and people who were pretending to be my friends, and my inner critic telling me I was an imposter.

When the fame bubble burst, rather than getting help, I went into denial and started self-medicating with drugs and alcohol for the next 12 years. In March 2007, rather than admit I was in a dark, dark place, I tried to end my life by overdosing on cocaine in a hotel room in Hong Kong. While I was unconscious, my then eight-year-old daughter Alex came to me [in my head] and told me to come home and get better. I woke up, and booked myself on the first flight back to New Zealand, vowing to turn my life around. That was the 1st of April 2007 and I have been clean sober and nicotine-free ever since.

Am I happy now? I don’t think I’ll ever truly be content or happy. I’m a driven perfectionist and we can never be satisfied. In saying that, I like the man I am becoming more than the man I used to be.

The moment that spurred my current trajectory in mental health advocacy happened in 2012, when I was asked by two colleges in Northland to come up and speak to the kids after eight young people took their own lives in the space of a couple of months. At the time, I was hosting a radio show called The Nutters Club where I would speak to people about their mental health journey, allowing listeners to recognise themselves in someone else’s story. Originally, I was going to go up, tell a few jokes and try and cheer the kids up but, when I got there, I knew jokes weren’t going to be appropriate. So instead, I shared my journey with mental health issues, focusing on the battles I have with my inner critic. You know — those negative conversations we all have with ourselves every day. What I didn’t realise at the time was, I was probably the first flawed adult these kids had ever met in their lives. After the talk, the kids were able to ask questions and I was blown away by how much they shared about themselves because they felt safe. That was my first lesson in the power of vulnerability, and it continues to drive me today.

The biggest problem facing kids today is an overactive inner critic. We all have one but for kids, it’s exasperating being surrounded by perfect adults who never talk about their doubts, fears and worries, yet constantly pick up their failings or minimise their mental health struggles. I mean seriously, your kids come home from school, tell you about five things that happened in their day, four of them are amazing and one’s bad. What do you focus on? Ninety-nine percent of us go straight to the bad.

We need to start sharing our vulnerability with our children. We need to talk about our doubts and fears because if we don’t, our kids will continue to believe they are the only ones who struggle and that is fertile ground for their inner critic.

I’m proud of Gumboot Friday. A platform that provides young people under 25 with free counselling. Currently, the only way kids can get free counselling is to go to a doctor, be diagnosed mentally unwell (a diagnosis that will impact their whole future) and then go on an excruciatingly long waiting list before seeing an often burnt out mental health professional. Gumboot Friday means people can book with three clicks of a button via gumbootfriday.org.nz and we pay the bill.

Over the course of my career, I’ve learnt life is full of ups and downs and things change so when a new opportunity comes along, don’t test the water with one toe — jump in with both feet.

My whole life, until now, the thing that has been missing is a sense of purpose. I need to feel needed, otherwise there is no point. I know that is wrong and it’s a character flaw — but it’s who I am and it’s who I will always be. I accept that now and I hope others can accept me for who I am.

Happiness for me is lying on a beach with my wife and kids soaking up vitamin D. I love summer and get really depressed in winter so it’s vital I get out in the sun when I can.

To anyone struggling, I would say “what do you need?” When people see somebody who is distressed, the first thing they usually say is “what’s wrong?” which implies you want them to talk about their feelings — and for a lot of people, that’s too hard. By saying things like “what happened?” or “what do you need?”, you are talking about their situation, which is easier to negotiate.

The part of my life where I felt pressure to present as more stoic than I feel is behind me. Now I’m comfortable just being me.

I feel optimistic about the next generation. Our kids are the most amazing generation of people in the history of the world. They are more empathetic, articulate, kind, understanding and compassionate than we ever were at their age and that gives me hope for the future.