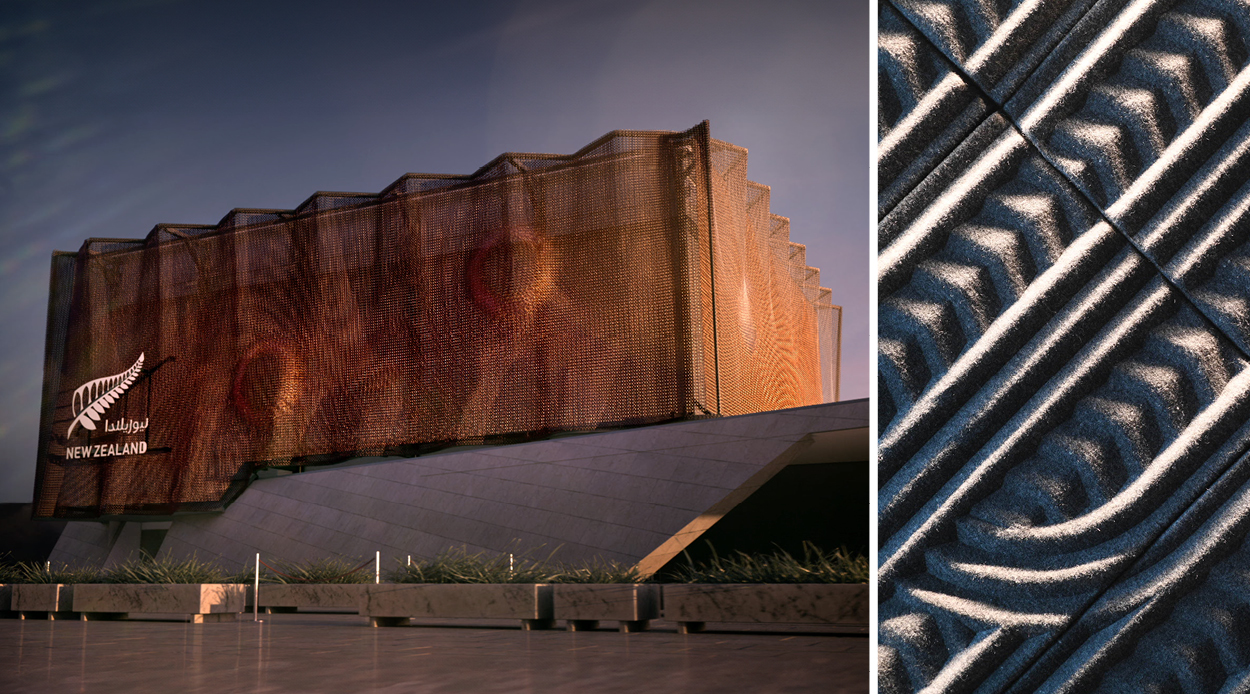

Even if you don’t recognise Karl Johnstone’s name, you would have felt his impact. Responsible for bringing a heightened cultural perspective to some of New Zealand’s most defining design projects — from St John’s Waka Manaaki ambulances, to Precinct Properties’ newest downtown development, to a pavilion at the Dubai World Expo — Johnstone draws upon the inherent dynamism of te ao Māori to enrich our cultural fabric, bringing a unique perspective to the creative pursuits that sets us apart on the world stage. With close to three decades’ experience working in the arts, Johnstone’s enduring success is down to a profound desire to contribute to our country’s forward momentum — and even with so much behind him, it seems he’s just getting started. We sit down with the multidisciplinary creative to discuss his philosophies, the future of Aotearoa’s built environment, nurturing our next wave of creative talent, facilitating enduring change, and the power of indigenous knowledge and design.

Karl Johnstone’s upbringing in Tūranga (Gisborne) was typical of those hailing from the East Coast — where the sunshine hours were spent outdoors; exploring, swimming, and surfing. It was an early relationship with the ocean that proved foundational to Johnstone’s career, as this is where he first developed a connection to the taiao (natural world). He talks of the meditative qualities of being in the water as the sun rises over the horizon; its light being captured in the folds of the local landscape, and this experience informing a deep connection to his place of origin — something that has influenced much of Johnstone’s work to date. “That moment of the day when the sun severs the night is where you connect to the intrinsic, inextricable link between people and place,” he muses. “There’s something special about looking back toward the land you descend from, while experiencing a greater connection to the revolutions of the world around us. In that moment, you realise you are bound to something much bigger than yourself,” Johnstone continues.

It’s also here, in his hometown, that Johnstone first discovered material culture and the arts, developing his passion for pigment and paint, and using this medium to strengthen and express his emerging whakaaro (identity-based philosophy). His love for creative expression and pūrākau (knowledge frameworks) inspired him to attend art school at Elam, before stepping into teaching back in Gisborne; a role he connected with, but felt restrained in due to the prescriptive nature of educational frameworks. “For me, it was never really about the singular process of painting, but about the process of putting ideas into form,” he muses. Next, he pivoted to institutionalised work, spending a decade at Te Papa — following which, he consolidated his voice in the cultural heritage sector as the director of the New Zealand Māori Arts and Crafts Institute.

This was all before starting his self-determined practice, Haumi; a specialist studio which initiates, develops and delivers projects of national and international significance in partnership with major organisations, iwi Māori and a network of international connections. Given the breadth of his scope, and the somewhat extrinsic tenet that informs much of his work, when asked to describe the nature of his creative studio’s output the answer is somewhat complex. “Our work has a foundational dimensionality and can’t be defined accurately within typical industry classification — it isn’t something that can be labelled in a binary sense,” he says with earnestness. The anchor, though, as has always been the case for Johnstone, is his origin and the connected lens with which he looks at the world: te ao Māori (an indigenous Māori world view).

At the inception of a collaboration, Haumi builds a creative strategy by considering provenance, context, and the intangible domain; storytelling and materiality are then nuanced through an iterative process. Harnessing the connectivity of te ao Māori is a partial, but fundamental part of these outcomes. The Māori lens helps to grow and strengthen a sense of identity, ultimately elevating our social and cultural dynamism as a nation. This has become an uncompromising aspect of Haumi’s work, much of which now centres on the articulation of identity — including within the built environment. In this space, Haumi collaborates with developers and architects to add a deeper sense of purpose to projects beyond their practical functions and creative forms. “Buildings are delineated spaces; they are a source of refuge; an opportunity to strengthen association; and are highly conscious in every aspect.” says Johnstone, “Our role is to ensure not only a positive aesthetic outcome, but a tenable depth to these spaces; creating an immutable sense of association,” he continues. “We use elements such as tone, colour, texture, form and fundamentally, a central narrative, to create and bind a building and its inhabitants.”

“Johnstone’s narrative direction inspired the ‘carved’ tower forms, acknowledging the three harbours framing Tāmaki Makaurau.”

Given Aotearoa’s bicultural foundation, ensuring indigenous voices are not only represented but celebrated — particularly within the built environment, is essential. And as such, Johnstone and his team are finding themselves working on increasingly more high profile projects. In 2022, Haumi was approached by Precinct Properties to collaborate on their latest downtown development. This impressive addition to Auckland’s cityscape, led by Warren & Mahoney Architects, is a project particularly close to Johnstone’s heart and an impactful example of Haumi’s work in practice. “With the foresight of Precinct and the support of Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei, this will be a space that becomes emblematic of the whenua’s history. It will be a symbol of confluence: of land and ocean, history and present; people and place.” Johnstone tells me. Working with mana whenua, Johnstone and the architects developed a unique narrative inspired by the Māori practice of whakairo (carving) — an approach that resulted in distinctive ‘carved’ tower forms that acknowledge the three harbours framing Tāmaki Makaurau.

Highly cognisant of the ability of art to unite people, Johnstone sees Māori narrative and artforms as having an important function in setting New Zealand apart on the world stage, and as such, has plans to extend Haumi’s scope further. When it comes to the immediate future, Johnstone and the team under his tutelage have many irons in the fire, but when I push him further on specifics (outside of hinting to a culinary project and the exploration of music as a medium of narrative building) he tells me that no matter the project, big or small, for him it all boils down to challenging and recalibrating conventions, and tethering to history in a way that maintains its integrity. “If we can inspire [those we collaborate with] to take risks and challenge the status quo, acknowledging intergenerational complacencies, we’ve done our job,” he says. Adding that, for him, the next stage of his career is about fostering the new wave of creative talent — passing the baton to the next generation to further this important work.

“The Māori lens helps to grow and strengthen a sense of identity, ultimately elevating our social and cultural dynamism as a nation.”

These days, Johnstone finds himself using any spare, quiet moments (there aren’t many) to think about what’s next for Haumi. Furthering the educational offering is likely on the cards (Johnstone already runs Ruawhetū, a charitable trust in central Auckland which includes a Māori wood carving school). It’s on a long list of possible endeavours whose common theme is to further strengthen the capabilities of rangatahi, and the development and perpetuation of Māori culture. “The challenge is to relearn what we know, and to move from systems of teaching that are at odds with the fabric of our culture. Knowledge derived from observation, lived experience, and the elevation of mana sits at the heart of the Ruawhetū kaupapa and will continue to inform our work for decades to come”, Johnstone tells me.

From deepening community connection to tangata whenua with the Waka Manaaki ambulances, to crafting narratives that inspire our country’s most notable buildings, and curating billboard installations that bring considered design and whakaaro to Aotearoa’s streets, Johnstone’s work is having a profound impact across all scales and disciplines. As our conversation draws to a close, I ask him if there are any misconceptions around what Haumi does. He considers for a moment, before saying, “Weaving cultural diversity and te ao Māori into design isn’t just about indigenous communities, it’s about enriching our collective identity as a nation.”

I finish by asking Johnstone what’s on the horizon for him personally. He says he’d like to find time to paint again, before launching passionately into his hopes and aspirations for the team at Haumi, and it’s glaringly obvious that Johnstone has his eyes trained firmly on the future — just not his own.