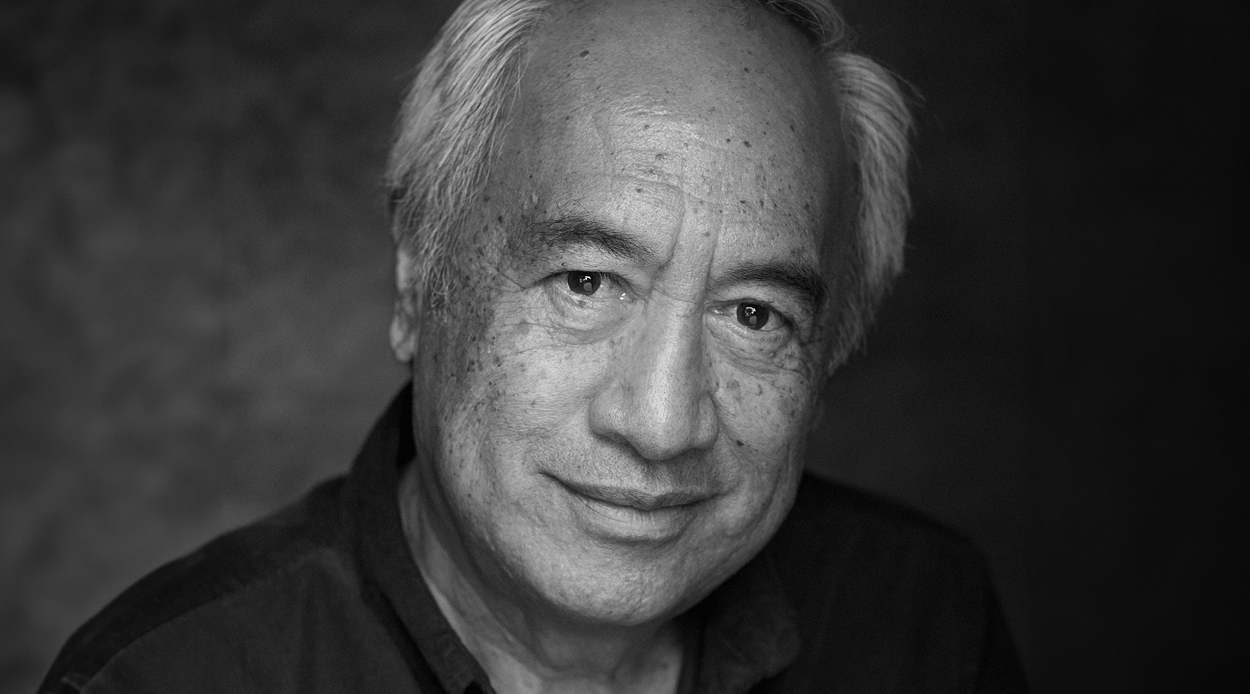

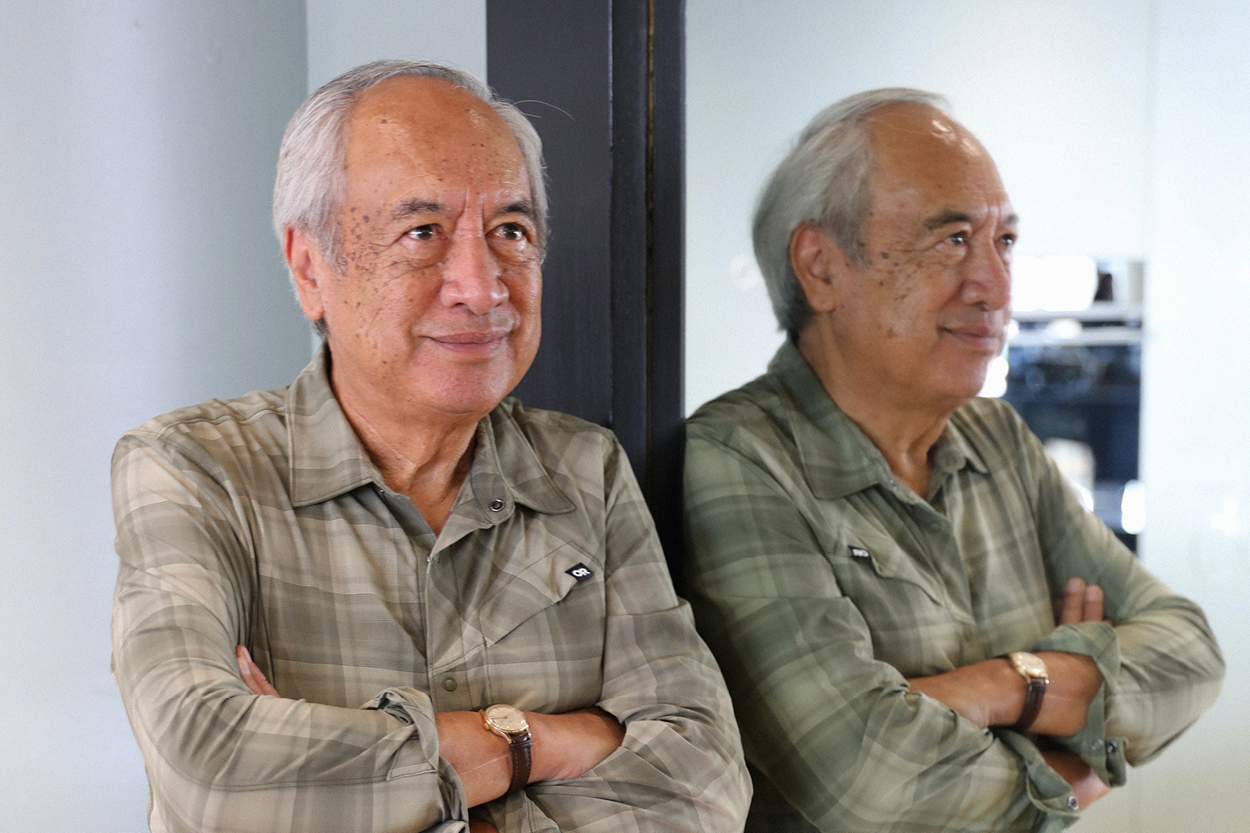

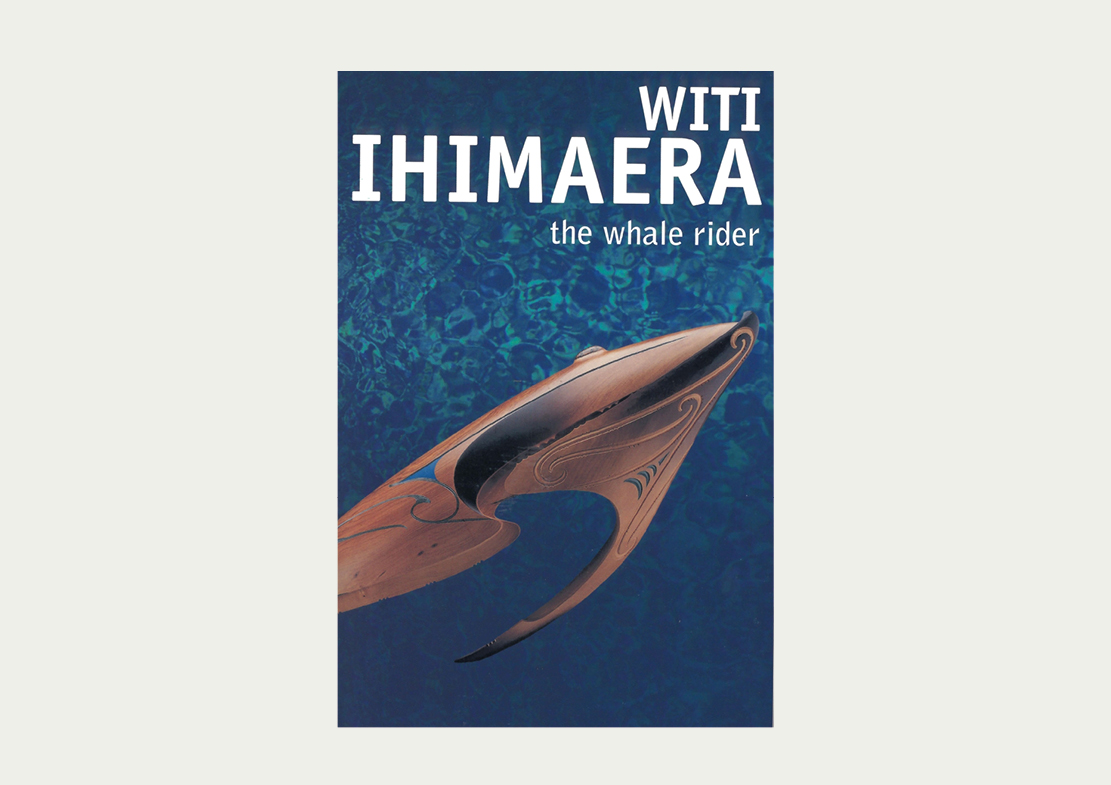

Even if you’re unfamiliar with his name, you’ll likely be acquainted with the significance and prose of Witi Ihimaera’s iconic book The Whale Rider. One of our country’s most celebrated authors, this year, Ihimaera celebrates half a century in the literary game, and to honour this milestone (even as he edges towards his 80th birthday) the author sat down with Tessa Patrick that this is the year of saying ‘yes’ to everything, including a world tour, three new releases and four audiobooks. Despite half a century of accolades and accomplishments, as well as a raft of learning along the way, Ihimaera’s career is only on the up. His works are internationally acclaimed, often translated into French and German (he takes great care to tell me that most of his stories transcend culture, despite being deeply rooted in a sense of Māoridom), and he finds himself, after all these years, with still more stories to tell.

One of the first things Witi Ihimaera confesses to me is his childhood dream. It was never to be a writer, really. (Although, as I’ll soon find out, the thought was always there.) His intention was to be a composer — one of the greats. But there was no piano at his flat in Wellington, and writing required far less bulky equipment. We’re at his home, listening to a piece of classical music by Sibelius, he tells me, and one of his favourite songs. He turns the radio up so I can hear what he says is the best part, which sounds like swans flying through the Finnish fjords. In fact, the author has just returned home from touring through Finland, Sweden and Germany (and Brisbane, too), talking about his 50-year-long career to those who have long-admired his work, which has been translated into a number of languages and is beloved around the world.

Although the dream of becoming a composer never took flight, Ihimaera still writes with a sense of musicality. There is something about his words that sing with literary lyricism. It’s intentional, he tells me, not a happy accident but rather the result of a young boy with something to prove. His later works have a more deliberate application of musical theory. “Literature should always aspire to the condition of music,” he suggests, referencing a quote he once heard in a lecture by author Anthony Burgess. “If I listen to the music, I always listen to my words the same way.”

In fact, there are many metaphors to which Ihimaera likens his words. Spirals, the seasons, the voice of his ancestors. Very few reflect his own tenacity and grit — the glass ceilings and prejudices he’s had to continually smash through in his career. While there are many great, and some critics might say arguably better, Māori authors — in front of me sits the first. The one to proudly defy expectations and the pathway set out for him.

Witi Ihimaera grew up on a farm outside Gisborne, nestled in a vast and staggering landscape. He tells me of his father, a farmer on the land, and the implicit expectation that one day he, too, would do the same. It took bravery to walk away from that. In the early days of his career, the author turned to his father and pleaded for support to return home from university and take six months off, and the space to work on his first novel. Here he faced the first of ‘no’ of many. Although he tells me that his father later came to him, recognising his talent and asking for forgiveness for not having seen it earlier. “I said, you know, Dad, your not supporting me was probably the best thing that could have happened because I was forced to achieve my own potential.”

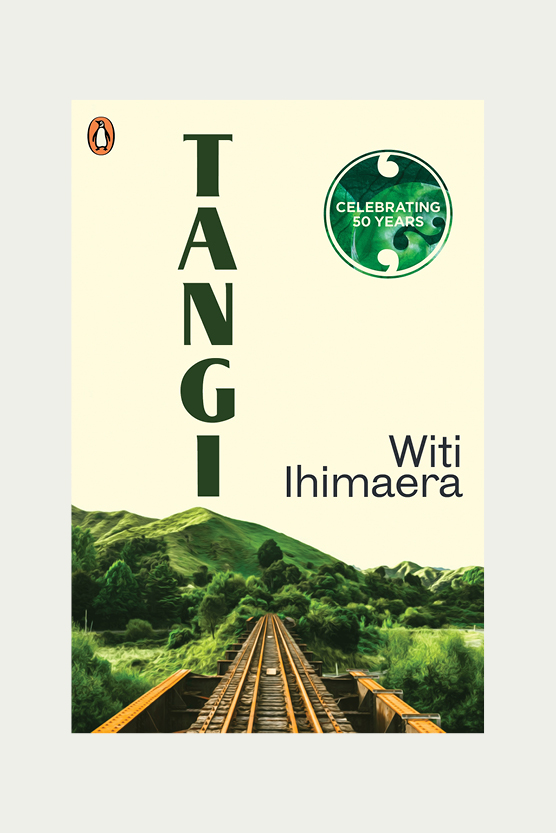

In the Tairāwhiti region, then and now, there is a rich and bountiful representation of Māoridom, which has offered the author a unique lens through which to see the world. “I often tell people, if you want to see my heart, go to Rongopai,” he tells me of his marae. The same marae where, some 50 years earlier, the bulk of his first novel Tangi finds inspiration. “I’m fortunate that the tapu nature of it never disallowed me from the work. I just love the world that I originate from.”

“As long as all of us, together, create a platform for New Zealand to engage more with the identity for itself that’s always been there, I will be happy to have been part of that.”

Since the earliest days of his career, the author has found it necessary to represent the Māori worldview to many. It comes with an overwhelming sense of pressure, he agrees, but it only stokes the fire. “What we’re all doing is legacy building,” the author suggests. “As long as all of us, together, create a platform for New Zealand to engage more with the identity for itself that’s always been there, I will be happy to have been part of that.” Offering his perspective, he tells me, was what he always set out to do. When we first met, I asked Ihimaera if he could pinpoint the single moment he knew he wanted to be an author. Most never have an answer to the question; it’s always a vague variation on ‘I think I always knew’. But Ihimaera did. He remembers the moment so vividly.

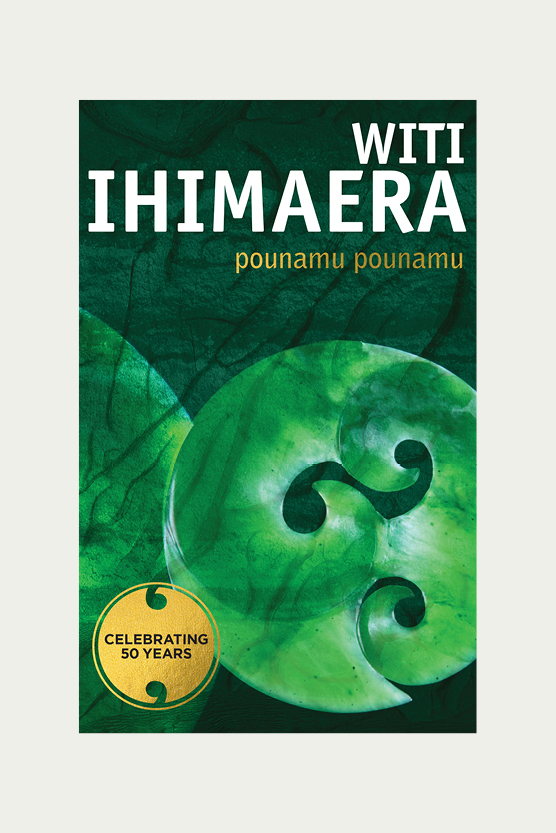

Elevating the Māori voice with more authenticity was always the intention. Ihimaera tells me the tale of how, at age 13, he read a story in school that presented a despicable depiction of his world. He threw it out the window and was caned as a consequence, but at that moment, he knew he wanted to write a book that told the legacy of his people with more respect. He speaks candidly about his experiences and success with a huge sense of appreciation for his career and all that it has afforded him. It wasn’t until some 15 years after the caning incident that Pounamu Pounamu, his first book (a collection of short stories that is still in print), was published, in 1972. From this point on, he tells me, “Māori writers had entered the room. It didn’t matter that I was the first.” Later this year, the book will be re-released in Te Reo Māori — the product of 11 different translators who Ihimaera has closely worked alongside.

Even on the brink of turning 80, Ihimaera possesses a constant desire to continue his learning — that’s one thing I came to realise quite early on. “The perfect full-circle moment, I will finally write a book in Te Reo,” he tells me. Despite it being his mother tongue, it’s not a language the author feels entirely comfortable writing fluently, just yet. Next year he will embark on a year-long Te Reo course to truly master the language in a way that will still do his literary brilliance justice.

There is something so nurturing about Ihimaera’s spirit. He is a guardian of his culture and of literature, but he refuses to put himself on a pedestal. Instead, he describes himself as “almost famous”, a notion I suggest might be a bit humble, but he doesn’t think he’s humble either, although sometimes he wishes he was. And that is true; Ihimaera is immensely proud of his work, and of how his works continue to evolve with the times. This is not to say that the themes have always been correct or fair representations. Somewhat unusually, he doesn’t see the first publication as the final version to be sent into the world — he knows that there’s always an opportunity to rewrite, to buy back books in some instances, and to continue to evolve the text beyond the page.

After all, that is why I am here now. Fifty years into his career, Ihimaera has recently released his third edition of Tangi — his first novel and his second published work. He tells me that with each edition, in keeping with the times, his work becomes richer and more representative of the world’s convoluted context. Should he live to see another 50 years, he’d likely rewrite all of his books some more (this isn’t really the literary norm, by the way). Take Tangi, for instance, which was primarily concerned with culture and custom when it was first published in the 1970s. He revisited the work in 2002, adding an extra layer of political context, and this year, it sees the reintroduction of Te Reo Māori throughout — an evolution about which he is sincerely proud. It makes you question what books can be; better seen as organic, living works rather than things that are fixed or rigid.

The most recognisable in Ihimaera’s catalogue is perhaps The Whale Rider — noted for the accolades garnered from its film interpretation as much as it is a formative text for emerging readers. (Many studied its significance in school.) For Ihimaera, it was a tale representative of so many events happening in the world at the time, a “spontaneous combustion”, he says. It was written over just three weeks during his diplomatic tenure in New York. “When I started all of this, I had no expectations or premonitions; you just write it,” he reminisces, reflecting on the larger landscape of the world at the time — a movement to ban whaling, to make New Zealand nuclear-free, the Antarctic treaty and the ever-increasing feminist lens through which people were viewing the world. “When I write, I grab everything out of the air,” the author tells me. “I never realised that I must have been grabbing all of these influences, bringing them out of the cloud, and putting them into the book at that time.” It speaks to the larger context of the story — the layers that we were convinced our English teachers were adding for the sake of it, which were really there all along.

Somewhat untriumphantly, Ihimaera tells me that he is finally working on its sequel — one that has been many years in the making. Not for fear of failure or the daunting task of the follow-up but because he can’t quite figure out how to tell the story with justice from a cultural perspective. He runs through the machinations of his draft, letting me in on the most intimate details of his creative mind, and unlike many other authors I’ve encountered, he is forthcoming in detail. Reading through emails between him and his editor, I learn more about the sequel. (The details of which are currently under wraps but promise a tale just as captivating as its predecessor.)

That said, despite some creative delays, Ihimaera is keen to keep moving forward. “If I take too long, I get sick; physically, mentally and emotionally sick,” the author reflects on his writing process, which he approaches at breakneck speed. “Normally, I will only write a first draft within, say, two months, three months. Drinking water all the time, karakia, going swimming and trying to keep myself healthy because, you know, it is a discipline that requires you to have robust health.” The Covid years, for Ihimaera, were less productive (contrary to what many may think). “I have to get out and talk to people and see how they’re feeling and what’s happening. So I didn’t write at all during Covid.” This leads us to the now, where after somewhat of a break, Ihimaera is writing again. “The feeling of catharsis is worth a million dollars,” he tells me of the process.

I get the feeling that wider public perception has never really concerned the author. “Some critics will say that I’m not a very good writer,” he offers. “And some of them will say, ‘well when we think about all the writers that are around, he may have a good reputation. But he’s not among the best of our writers.’ Well, I just don’t give a fuck. They can think what they like, but I’m just happy to articulate the condition that I see.”

As brilliant as his works may be, the author positions himself strides away from perfectionism — allowing himself the space to play and grow as his career evolves. “Sometimes I will get as far as eight drafts and look at that eighth draft and think, wow, this is really perfect, it’s got so much excellence, and it’s thrilling. And then my spontaneous brain will say, but you’re not as perfect as all of that. That’s not the one you should publish — go back one. I consider it more reflective of who I am as a writer.”

It’s fair to say that he understands the severe responsibility of the role, and always has. He shows recognition that, in fact, he should be concerned with the public perception, but the duality of his nature encourages him to pave his own way. Constantly. For as long as he is writing, his work will continue to evolve. He also knows when to accept wrongdoing — or fault — and the correct way to atone for that.

“I had a book called The Trowenna Sea, which went through a huge controversy here in New Zealand,” he confesses. “I don’t think any other author has been through this so much in terms of the accusations based on their plagiarism.” The incident was never intended as a malicious or deceitful attempt to take from other authors. Instead, excerpts were insufficiently attributed to their authors. An innocent oversight — but enough to cause significant ripples in the literary realm. Ihimaera bought back all the copies of his book after it was brought to his attention, an attempt to atone for the blunder. “And I did apologise. But it turned into a bigger thing than it really should have been. Those kinds of things make you angrier and stronger. You go back to your method, you go back to your technique, you go back again, and you revise. You start learning all over again, you look at your methodology, and you critique it. And then at those points where you see what the mistakes were that led to this, you retrain yourself.”

The first time I met Ihimaera, we were attempting to get to know one another between filming various media calls for Auckland Theatre Company’s season of Witi’s Wāhine and courses of Peter Gordon’s insanely delicious hangi pork belly and homemade pavlova. It wasn’t until a month later when I reached out again to continue our interview, that we agreed we could have kept talking all day. I had said to him that it felt like we barely scratched the surface, which was true. After all, how do you condense a 50-year career and all its necessary context into a 30-minute interview? The next time we met was at his home in Herne Bay; a glorious villa where the mid-century spaces were filled with exquisite, Māori sculptural art. There was coffee, croissants and cake shared, and despite two hours spent talking, I felt there was still so much curiosity around the author. Perhaps he’s one of those subjects that raises more questions than answers.

And while Ihimaera loves to talk about himself and his work, he became most lively when the subject turned to me; my aspirations and curiosities about the world. In one manner, he returned to teaching mode, reflecting the years he spent lecturing at Auckland University, and offering me advice quite unlike any other. He was genuinely interested, engaged and so innate a storyteller that every answer he gave me was thoughtful and considered; every tangent (of which there were plenty) took me on a thoroughly enjoyable journey into his work, his perspective and his past, so much so that I cast aside most of my prepared questions — what he had to offer was greater than any prompt on paper.

Ihimaera’s approach to his craft teaches one that in the face of it all, few things are as fixed as we think they are. “If I live another 50 years, I’ll probably rewrite it all again,” he reflects. What a joyous way to live. Our time together (for now) ends on that note. I walk away with a promise to keep the author informed of my own writing endeavours and perhaps even a new mentor to offer a fresh perspective when I seek it most.

The interview closes on what I can only describe as a storybook moment, when Ihimaera leans over his balcony as I’m leaving. “Don’t forget to just keep writing,” he calls after me. “You will love it even when it hurts.” He explains that there is nothing more fulfilling than writing your world and someone else out there, maybe a stranger, recognising it. And with half a century on me, who am I to disagree with his sage advice? So I resolve to continue to do so. After all, how much richer have our lives and culture been made by contributions from artists like Ihimaera? His compassionate and contextual work has become more than a literary cornerstone, it has evolved our understanding of the world around us. And I must say, we’re collectively better for it.