For the uninitiated, the metaverse can feel like an unassailable concept; complex and ever-evolving. And while Facebook’s recent name change to Meta (which many have argued is a strategic move by the company’s embattled CEO to pivot from scandal) has dominated headlines, the metaverse is broader than what one social media juggernaut alone is offering.

The central idea of the metaverse proposes that virtual worlds (digital havens in which people can purchase products, buy land and socialise with one another) are the future of the Internet, but its development gives rise to the question of how blurred the lines will become between our ‘real’ world, and the one we can inhabit online — and how the two can coexist.

So what is the metaverse, exactly? Broadly, it refers to the ways in which our interactions with technology are changing, and it will affect how we socialise and how we do business. To look at it structurally, the metaverse comprises virtual worlds, augmented reality and a growing (and thriving) digital economy. According to Cathy Hackl, a prominent tech futurist who helps brands prepare for this new technological frontier (she has been called ‘the Godmother of the metaverse,’) it is “…a further convergence of our physical and digital lives… It’s about shared virtual experiences. It’s about breaking free from two dimensions into a fully 3D environment.” For Hackl, the metaverse makes the impossible possible. It is the successor of the Internet, and it promises the kinds of opportunities for businesses and creators that have never existed before.

The Internet of old is set to transcend the tools we use to access it (phones, tablets and computers), and is morphing into something immersive and truly omnipotent. More than something we can see, it will become something we can experience and feel. Which will probably make it much harder to switch off from. And perhaps that’s the point.

But before we get carried away, it must be said that the metaverse is still more or less a fictional space. A wealth of ideas but a distinct lack of infrastructure (the software and hardware both have a way to go) means that it doesn’t really exist yet. And because the metaverse is still in its infancy, any attempt to define it would be like someone in the 80s waxing lyrical about the Internet — pointless and destined to be proven wrong. Really, the virtual spaces that do exist now, in games like Fortnite and on platforms like Decentraland are simple and rudimentary. And despite there being a lot of speculation (including some pretty serious financial speculation) around the potential of the metaverse, no one really knows what it is, or crucially, what it could become.

We can only really discuss what we’ve seen already, which has included the rise of cryptocurrencies, the proliferation of NFTs and the beginnings of what some are calling the new goldrush — a virtual real estate boom. In 2021 alone, over USD$500million of real estate was sold on metaverse platforms, and that is predicted to reach USD$1billion this year. Let that sink in. Brands re-evaluating their footprints are quickly realising the commercial potential of virtual land. Not only will it open them up to literally millions more customers, but it offers a level of versatility and freedom that any brick-and-mortar storefront could not. This has huge implications across a number of industries, including luxury fashion, arts and culture — all sectors that have traditionally relied on real-world interaction for their bread and butter.

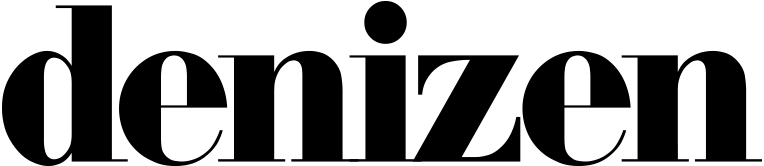

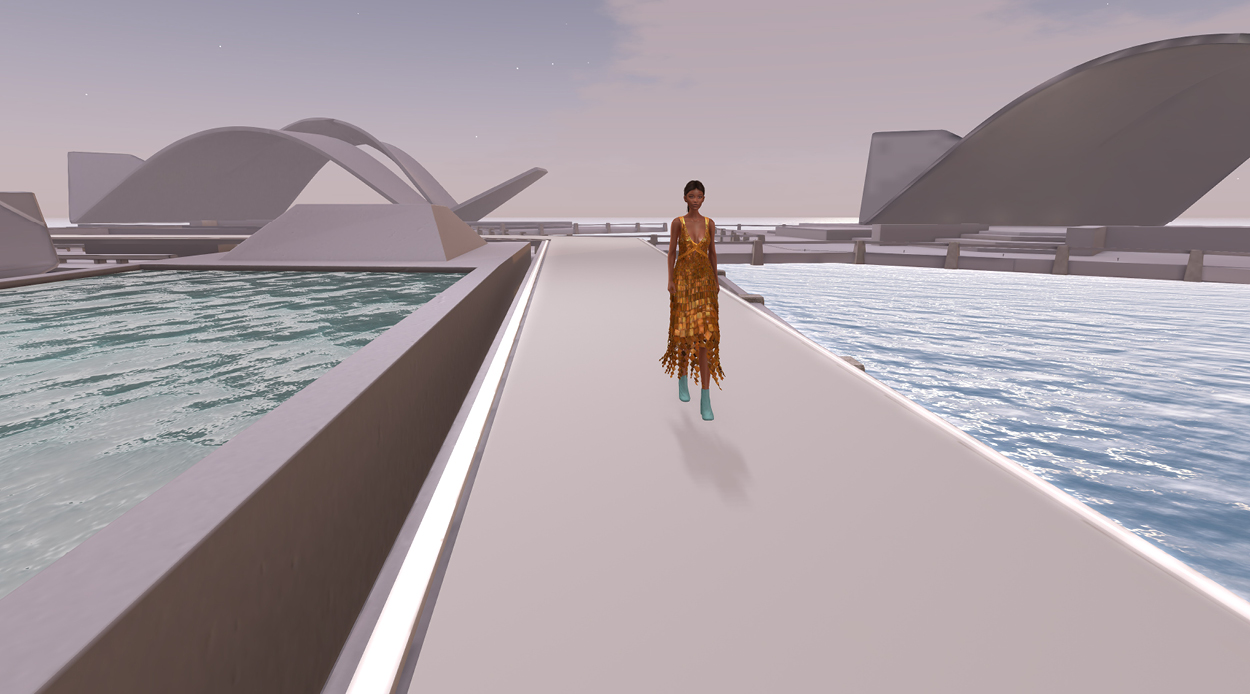

Fashion, in particular, seems to be embracing the metaverse wholeheartedly, with luxury labels rushing to make their virtual mark early. Major metaverse players like Decentraland are already boasting fashion districts in which people can shop, as well as creating virtual events like Metaverse Fashion Week, which will see platforms teaming up with big-name designers to create virtual shows and sell digitally-rendered collections. Jonathan Simkhai and Roksanda are two labels that entered the metaverse for their most recent fashion week outings after a number of successful events last year proved the profitable potential of this new frontier.

One example was Gucci’s ‘The Gucci Garden’ on metaverse gaming platform Roblox, which saw the brand selling virtual products for real money. A classic Dionysus handbag sold for around USD$4,000, which is actually above the retail price on the ones that can be carried around in real life. Balenciaga also released a collection last year with gaming platform Fortnite, for which the luxury house created a series of ‘skins’ that players could purchase for their avatars. And Dolce & Gabbana at its Alta Moda show released a separate collection alongside its real one in which each piece was attached to its own NFT. The combined sale price of the collection at auction was USD$5.7 million. There are even metaverse department stores being launched like British start-up The Dematerialised, whose founder envisages a future where consumers’ virtual wardrobes are bigger than their actual ones.

For fashion brands, the metaverse is an exciting (and very real) new revenue stream that promises big margins with minimal resources, and no pesky leftover stock. It also offers ultimate freedom. In the metaverse, a dress or a t-shirt doesn’t have to abide by the laws of physics. And when functionality is no longer a requirement, clothes can be whatever their designer wants them to be.

It is a similar story in the world of arts and culture, which has seen the rise of NFTs, (Non-Fungible Tokens, digital identifiers recorded in a blockchain that are used to certify authenticity and ownership) open a hugely profitable new market for artists and auction houses. Sotheby’s recently established itself in the metaverse by creating a permanent space in Decentraland, while Christie’s teamed up with the world’s largest NFT marketplace OpenSea, to offer curated auctions to NFT collectors around the world. Even New Zealand artists are getting involved. Last year, Auckland-based auction house Webb’s sold the NFTs of two original glass-plate negatives of a photo of Charles Frederick Goldie for a combined NZD$127,000 — a sum far higher than expectations. And beyond the auction houses, it’s artists who are able to really capitalise on the NFT craze. This month, a new NFT marketplace called Glorious is set to launch in New Zealand, which will team up with well-known artists and creators to help them sell NFTs of their work.

But it isn’t just NFTs that are drawing people in. Virtual art experiences and concerts are offering a whole new way for people to engage with culture. At the end of last year, Justin Bieber held a metaverse concert on the virtual music platform Wave, where audience members could interact with the hitmaker’s avatar. Elsewhere, renowned museums and art galleries around the world are looking to see how augmented and virtual reality might enhance visitors’ experiences and interactions with their exhibitions.

Beyond the bottom line, the metaverse promises artists more control over their work and how it is consumed and sold. It could also see a fascinating new subsection of digital creators coming up with art forms that have never previously been possible, and bringing with them a new demographic of collectors and critics from outside the traditional body.

This speaks to the broader picture of why the idea of a metaverse is an appealing prospect. It not only promises creativity and an escape from the bounds of reality, but it offers a chance at transformation. It democratises spaces that, in real life, can feel inaccessible and elite. That’s the idea, anyway. It will be interesting to see whether this vision of egalitarianism can hold true once more and more people enter the space. Money still talks as loudly in the metaverse and there, profit is power.

Importantly, most discussions of the metaverse leave out crucial questions of governance, surveillance, data security and personal safety — one woman reported having her avatar groped within minutes of her being in Meta’s metaverse and there are apparently issues arising with young children using platforms they shouldn’t and the related risk of sexual predators. None of those things have been addressed yet. In short, there is still a long way to go before the metaverse lives up to the vision of its proponents, beyond all the marketing hype.

But as technology weaves itself more deeply into the fabric of our everyday lives, we can’t help but wonder how far-fetched the idea of us living in a virtual world is, when our current reality is already so augmented. And as we become more reliant on artificial intelligence for connection, socialisation and business, the metaverse feels less dystopian and more like our next evolutionary step.