Lucas Jones is a big thinker. A deep feeler. An artist in the truest sense of the word. He creates from his heart and seems entirely unburdened by vulnerability, but his magic goes beyond that. He possesses a unique ability to tap into the zeitgeist; the cultural consciousness; the depths of the human experience. He distils feelings that, to most, are impossible to quantify, into a universally-understood language — delivering those words via his myriad creative outlets (poetry, film, music). Lucas Jones is the moment. But not in a romanticised, online way. In the real world. He embodies the moment, he gives it a voice; making it mean something.

In a world full of dissociating, avoidance, and farce, his words are a vessel; a mirror he holds up to society, showing us what we often fail to see for ourselves: that all we have is now.

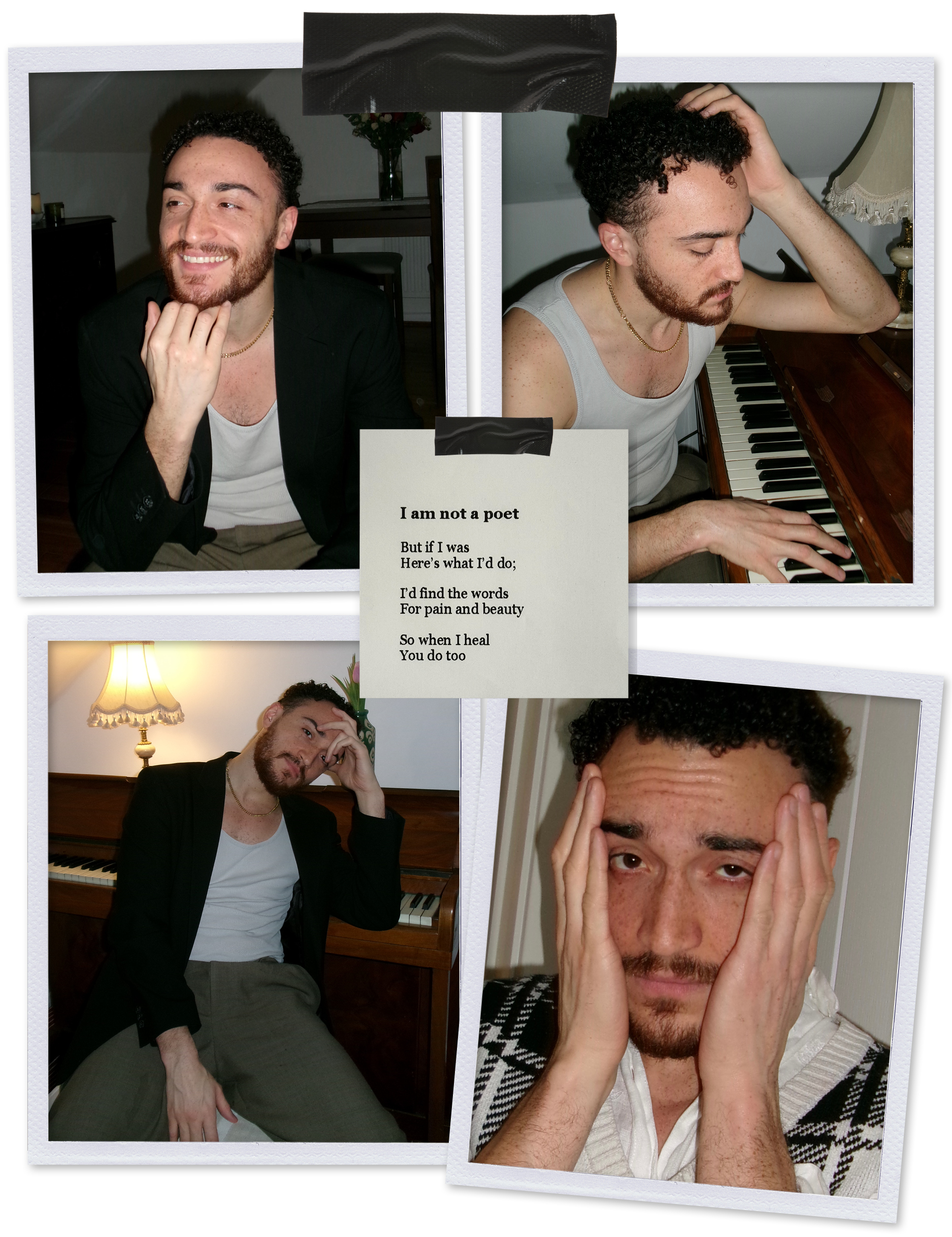

Popping up on my screen at 8.30pm on a Wednesday night, despite the two dimensions, Lucas Jones’ presence is enormous. Taking in his background, I’m met with a familiar sight: Jones, wearing what has become his signature loose-cut blazer, white singlet, and silver chain, curls in tight rings atop his head. He’s sitting in front of a weathered wooden piano. It’s a scene I’ve taken in countless times on his Instagram, and I’m hit with a comforting wave of déjà vu. At one point during our conversation, he reaches out of frame for a book of poetry to quote a specific work, and I’m overwhelmed by the desire to see what’s beyond the screen’s view. But that’s the thing about Jones. He always leaves you wanting more.

Growing up, predominantly, in Huntingdon — a small town in Cambridgeshire, north of London, Jones’ childhood was one of perpetual movement. He’d lived in seven houses by the time he was 14, “I don’t really know why we moved so much,” he admits. “I think my mum just loved newness.” That restlessness shaped him in both obvious and unexpected ways — he learned to integrate, to adapt, and, perhaps most notably, to observe. “I had this fear of people when I was growing up, but I was good at figuring out how to fit in.”

Huntingdon, Jones tells me, was a dichotomic place, and he spent time on both sides of the tracks. “There was a stark difference in how people were living where I grew up. Some were at home baking apple crumble, while, just one street over, teenagers were getting stabbed on the side of the road.” A lot of the boys he grew up with, “sweet natured boys,” never quite made it to the right side of town.

School was a difficult period for the natural-born creative, who felt he never fit into the binary box the system was so desperate to squeeze him into. “I remember being five and thinking, ‘I have to do this forever?’” He laughs, but the sentiment lingers. “I couldn’t wait to be 19. I thought then, surely, I’d have some kind of agency.” School, he tells me in his prosaic way, felt like a gaping void. “It’s kind of like this swirling black hole in my timeline,” he says, pausing before returning from wherever his memories had taken him.

At school, he felt restless, bored, and fundamentally underutilised. I point out the ways in which I feel the schooling system has long been failing young boys, and he seems liberated, “I had too much energy and too little focus. Sitting in a chair all day felt like going against my basic human nature… and the frustration from that definitely led to some push back.”

Just as things were starting to look bleak, a glimmer of hope came in the form of an English teacher who recognised Jones’ talent for words, sparking his first flicker of creative purpose. “We had this assignment to write a headline for a fake news story about a terror attack in Paris. I wrote, ‘Eiffel Terror.’” He pauses. “And the teacher went, ‘You’re good at this, you’re good with words’” It was the first time he can recall someone in the schooling system validating his belonging, and Jones (ever the big feeler) tells me how that moment lit a thousand fires within him.

Next came poetry, “We had this little anthology in class, and you were meant to study five poems. I read the whole book front to back. Even the ones I didn’t like — I just thought, ‘This feels like it means something.’” His mind has been ablaze with the quiet poetry of life ever since. One of the anthology’s poems in particular, a sardonic work by Simon Armitage (Poem, Poem) has stayed with him all this time, and informed much of his own creative work.

Soon after he discovered creative expression, drama provided a similar escape, “It was a break from school for me. A chance to just… play.” When he finally left formal education, Jones enrolled in a performing arts course, where, for the first time, learning didn’t feel like an obligation. “I never missed a day. I was completely lit up by it.”

After college, he hit a bump in the road. Many of his contemporaries were continuing on to art school, but the confines of institutionalised schooling in that capacity didn’t feel right for him. But if not that, then what? He decided to go all-in with acting, “A Will Smith quote I heard when I was 14 came into my mind: ‘Never make a plan B because it distracts from plan A’, and I just quit my part-time job and dove into it head-first.” It happened slowly, bit-by-bit (as it almost always does). Jobs as extras turned into commercials, small parts in TV shows turned into bigger roles, and his profile, along with his confidence, grew.

Acting, far from a route to fame and fortune, was simply another outlet of creative expression for Jones — a way to become more deeply immersed in the cinematic world (an altar at which he worships). “[Film is] almost a religious thing. For me, the reason people congregate at church is the same reason people congregate to watch films — to share something meaningful. I honestly think storytelling and film making is a God thing.”

While on the topic of religion, Jones — who possesses a faith — tells me of a quote that has informed much of his work. I haven’t stopped thinking about it since. “Even if the Bible isn’t fact, that doesn’t mean it isn’t real.” The sentiment and principles of the pentecostal doctrine he grew up around have long lingered in his mind; moved and inspired him, as much of what he consumes does.

The multi-faceted creative has long been aware of his sensitivity to art, “I saw The Wizard of Oz when I was four, and I remember crying out in absolute terror. Dorothy wasn’t going to make it home, and I thought, ‘How will I survive if she doesn’t?’ I was just so absorbed in the world that was being created, I couldn’t separate it from reality.”

Growing up, Jones developed a number of unique practices around film that, in hindsight, hinted strongly at his future. He and a friend were given cinema cards, granting them unlimited access to films, and at the age of 14 — instead of seeking out action epics and the latest blockbuster, they’d find the most moving, soul-stirring cinematic work they could, and sit together in the experience and cry. He laughs, “It became this weird ritual.” When he wasn’t baring his soul at the theatre, Jones was engaging with similar films at home, where he would get into character and write monologues in the protagonist’s voices. “I think I just wanted to absorb the films entirely. I wanted to burn every little neuron of it out of my experience, I needed to take in every last inch. I still do.”

That ability to sit with art, to let it pervade and shape him, is perhaps why his poetry is so widely resonant. His work is raw, unembellished, direct — almost confrontational in its emotional clarity. But his writing process — given the enormity of his eventual work’s impact and the depth and surety with which he writes — is surprisingly relaxed. “I write most of my poems in the shower,” he says. “Some start and finish in one.”

I Will Teach My Boys To Be Dangerous Men — one of his most well-known and widely revered works, was written in that way. “It was 30 minutes, and I didn’t allow time to overthink it. I just trusted my first instinct.” That instinct, sharpened by years of consuming and creating art, is what makes his words land with such resonance.

Jones began sharing his poetry on Instagram in 2023 as a way of putting more of his art (and himself) out into the world, pushing himself to be more vulnerable. But the initial cost of expression was high, and the hate was relentless, “People were in my DMs telling me to kill myself.”

The internet, for all its connective power, can be brutal. But Jones refused to be deterred, “Fear, to me, is a direct indicator of growth,” and art, he’s certain, is there to challenge people. “I think if people aren’t a little agitated or confused by what you’re creating, you’re likely not pushing hard enough or being honest enough.”

And over time, as it always does, the tide shifted. His reels started reaching more people; resonating more deeply. “One day, I got a message from a man who said he was about to jump off a bridge. He was sitting on the side, waiting for cars to pass before he jumped. He had his phone out, scrolling to look casual and not attract attention, and my poem popped up. Because of the words, he didn’t jump.” He exhales, “That. That’s the point of it all.”

When it comes to social media as an outlet for creativity, he believes it’s a double-edged sword. “It’s changed my reality,” he tells me, but carefully adds that he’s one of the lucky ones.

“I think [social media] is net good at the end of the day. At the very last minute of the day, it’s good.” But, to get to that place, Jones emphasises, you have to wade through a treacherous sea of over stimulation and toxicity. “If you don’t have people in the real world who love you, and you confuse social media for reality, you’re done.”

Social media, and the poetry which has amassed him nearly half a million followers and reached millions more, is just one part of a broader creative ecosystem for Jones. “Film is my true love. Poetry has given me autonomy, but everything I do is ultimately leading me back to storytelling in film.” He recently released a project he’s deeply passionate about, his directorial debut — Winner Fights the Moon — an award-winning short film centred on a man trying to turn the tides after incarceration, held back by the past. And when we talk, he’s in the throes of writing his first feature. It’s evident how much this work means to him in how he lights up when discussing it, “I want to tell stories about people the world forgets — boys who had potential but no direction, the ones who just needed someone to tell them they were good at something.”

He tells me he’s constantly advocating for them (the lost boys), “It’s fine to get mad when someone fucks up, but then we need to ask why. Someone’s gotta go back for the boys, someone’s gotta say there’s a better life, by the way, there’s a nicer life out there.”

That people across genders, races, classes and oceans can see themselves in Jones’ work speaks to his unique capacity to distil the beauty and brutality of being human into words.

The complexity of the human condition is a recurring theme across the breadth of Jones’ creative canon — specifically, exploring gender and bias, tapping into his unique upbringing and the learned wisdom that belies his 28 years, “I grew up around strong women,” Jones tells me, before recounting that until the age of 10, he thought women ran the world. “Growing up, dad was often away working in London. I always felt his presence, and he was a super active, loving, and supportive dad who always found time to foster my talents, but he wasn’t always physically present, so I saw my mum managing the world around me. I just thought the world was run by kind, capable, intelligent women who brought out the best in everyone around them.”

His father, a former diversity trainer for the Metropolitan Police, modelled a deep respect for others, and has undoubtedly been a catalyst for Jones’ capacity for kindness. “He trained over 30,000 officers in how to interact without bias,” and he brought those same lessons into the home.

That upbringing shaped his world view. “I was always baffled by overt misogyny. It’s like, ‘What world do you live in?’” His poetry, often labelled as feminist, is really just an extension of that perspective. “It’s not radical. It’s just… people matter. Women matter.”

But his exploration of masculinity extends beyond advocacy for women. His poetry and cinematic work seeks to unravel the complexities of what it means to be a man in today’s world — the expectations, the fears, the learned behaviour. He writes beautifully and poignantly about the ramifications of generational trauma — the cyclical nature of anger, fear, and the complexities of emotion, and how those things can break or make lives.

His piece I Will Teach My Boys To Be Dangerous Men is a quiet manifesto. “It came out in a rush, like so many of my poems do. It’s about breaking cycles — letting boys be whole, not just tough.” The reaction was immediate. “Men messaged me saying no one had ever told them it was OK to feel before.”

In this respect, Jones doesn’t just challenge traditional masculinity, he reimagines it. His poetry, stripped of ego, leans into honesty, his voice vibrating with emotion as he speaks to what clearly means so much to him, “I want men to know they don’t have to inherit the worst parts of what came before them. They can choose something better.”

This begs the question, are his poems personal? He thinks on it for a minute. “It’s more something I’ve sensed someone else feeling, and I can relate to. I find it hard to think about how I’m feeling in the moment, but easier to think about other people’s experiences.”

But while his work is not autobiographical, he certainly draws on experience. Perhaps the experience is just more universal than personal. In fact, one of the most fascinating aspects of Jones’ work is that, while much of his writing is centred on young men, the diversity of his audience is immense. A new mother in South London grappling with identity finds the same level of personal resonance in his work as a seventeen year old boy in Birmingham struggling with mental health. His fecund words — both timely and prophetic — build a bridge for others to cross.

Brick by brick, word by word, he articulates the ineffable; gives shape to the formless, “I think words are a way to take something overwhelming and make it less so.”

When it comes to what’s next, Jones refreshingly tells me more of the same. He’s living out his dream, spending his days creating and making art he believes in. For a person wholly devoted to expression, there’s nothing more or less than that.