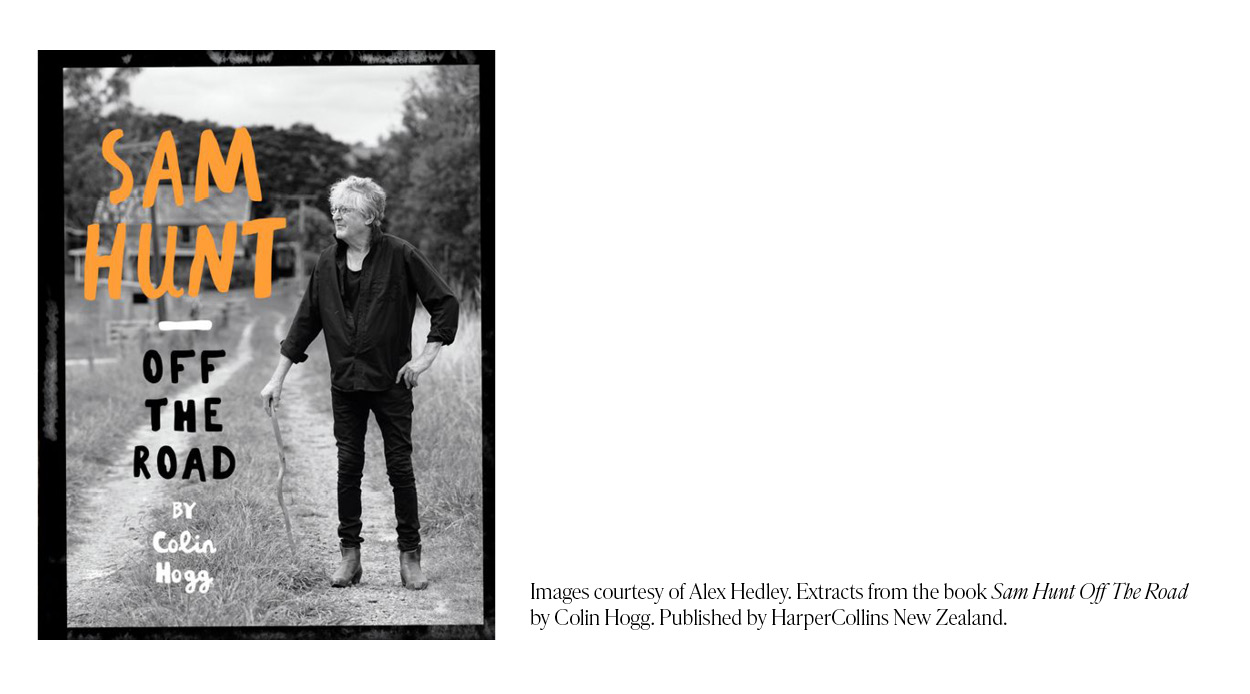

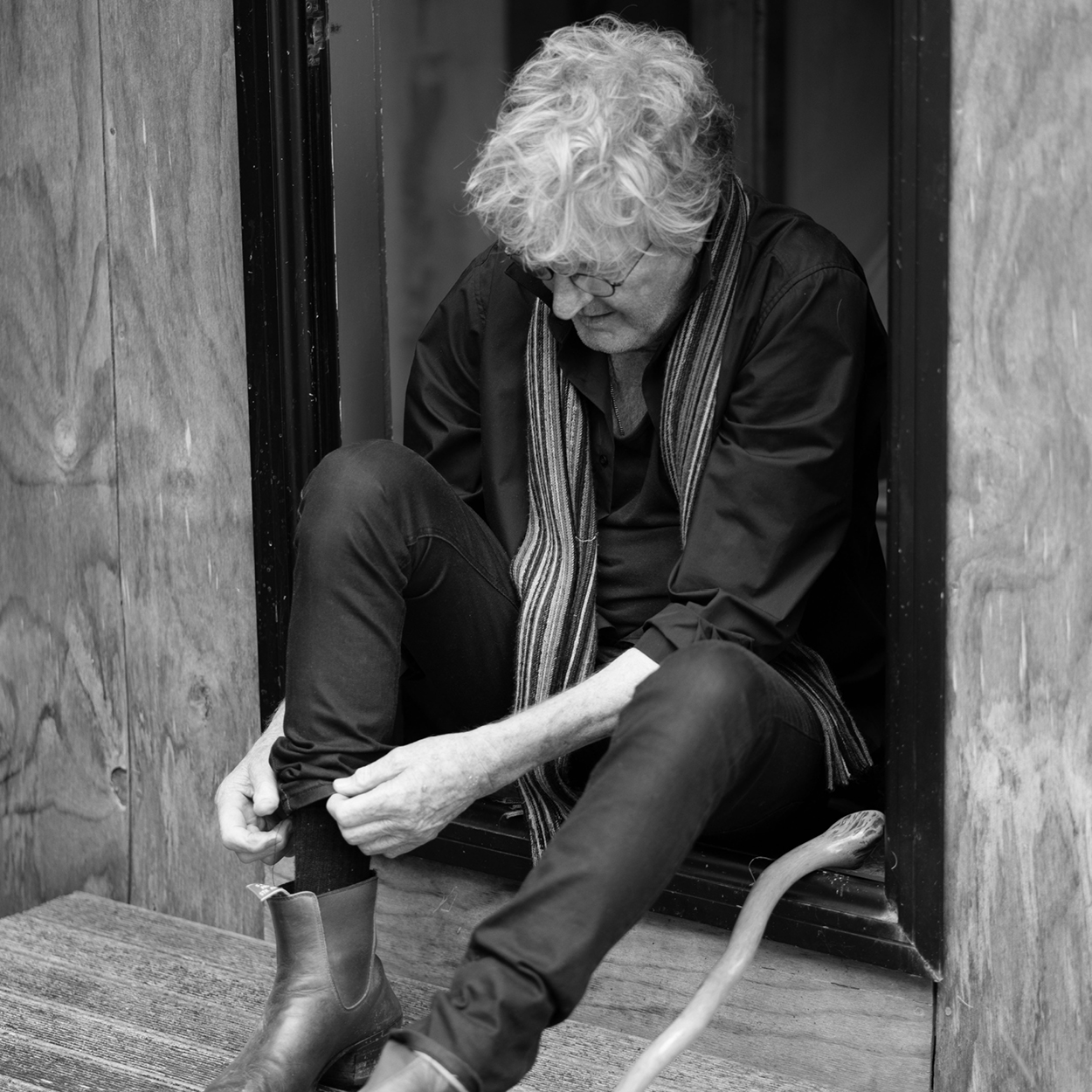

He is one of New Zealand’s most iconic figures, but don’t expect Sam Hunt to take up that lofty mantle readily. While over 50 years of writing and performing poetry has seen Hunt’s work come to hold an incredibly important place in our wider literary landscape, he is not interested in waxing lyrical about his legacy or acknowledging the influence his distinctive voice holds. For him, the idea of a ‘career’ sits at odds with his work, which he would tell you is something that has just been in his blood since childhood.

Impressively, poetry has been the way that Hunt has made his living since he started touring the country in his early 20s, frequenting pubs and venues up and down New Zealand to enthral audiences with his spoken-word performances, and making a name for himself with his shaggy-haired, lovable-rogue presence. (He officially retired from performing five years ago.)

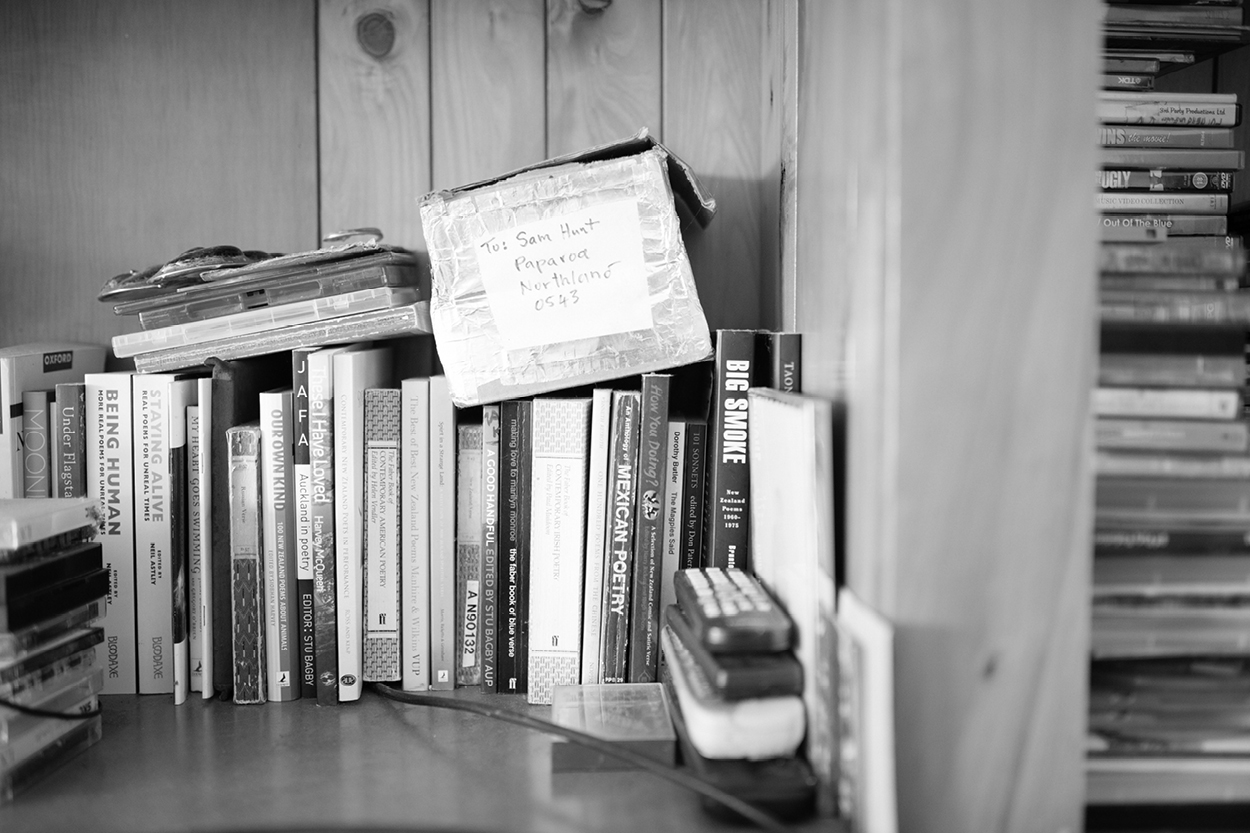

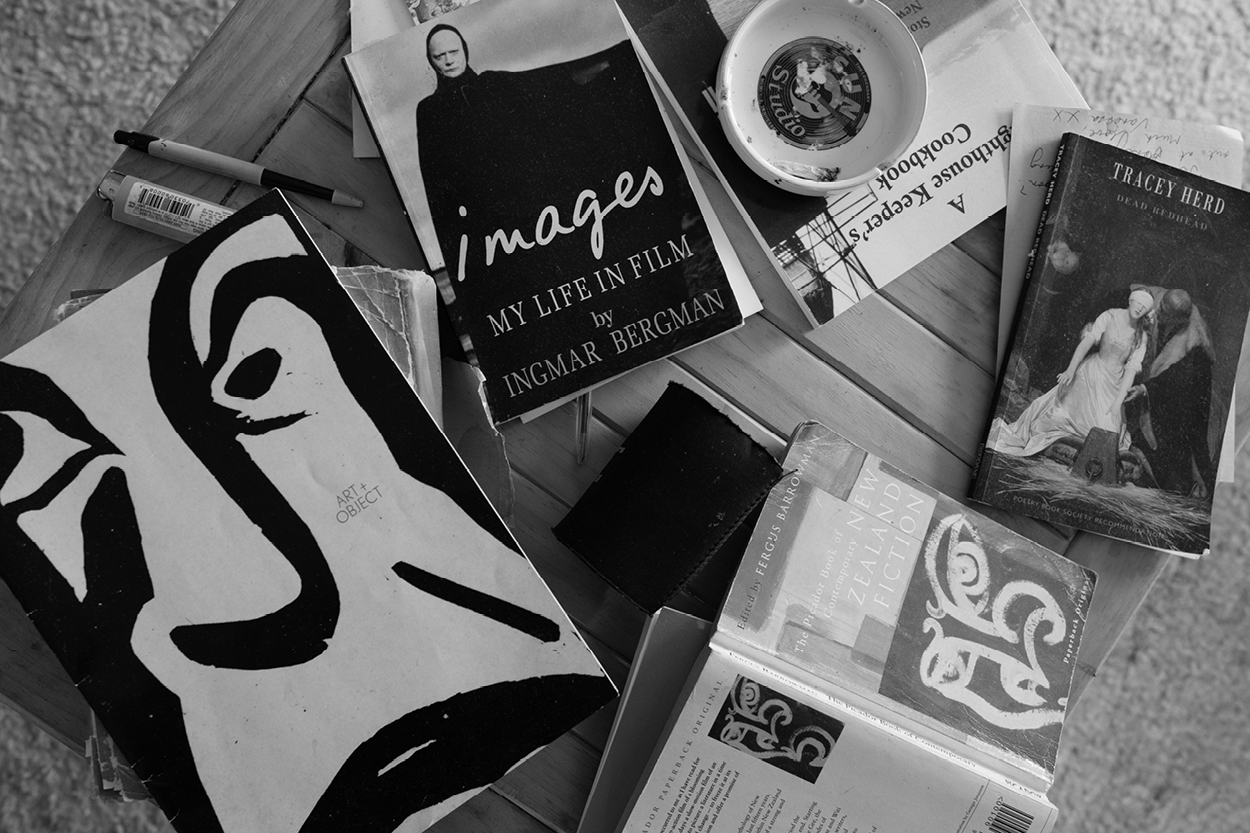

Over the years, he has published numerous books and anthologies, his work has inspired a documentary film and he has had a number of articles penned about him in which he has been painted as a rakish character and a true bard — both true. But more than all that, poetry is something from which Hunt just cannot escape (and he doesn’t want to either). It is more than just a way for him to express his experiences; it is a lens through which he looks at the world, where a conversation with Hunt will see him recite cantos and lines from a mind-boggling number of other writers’ work — all of which (and thousands more) sit comfortably in his memory.

Here, we sat down with the man himself to discuss his fascinating poetic process, the lyrical voices that run through his head, the beautiful stillness of his home on the Kaipara Harbour and the crucial importance of listening.

As long as I can remember, poems were part of the scene at home. My parents both loved poems, but different sorts of poems in different sorts of ways. If I could put it plainly, my mother’s favourite tipple was the lyrical poems, whereas my father’s great love was for the ballads. He used to tell me ballads like Lord Ullin’s Daughter:

A chieftain, to the Highlands bound

Cries, “Boatman, do not tarry!

And I’ll give thee a silver pound,

To row us o’er the ferry!

“Now, who be ye, would cross Lochgyle

This dark and stormy water?”

“O, I’m the chief of Ulva’s Isle,

And this Lord Ullin’s daughter.

And so on and so on. Wonderful. So I grew up with all of that.

When I was seven my mother converted to Catholicism and I became an altar boy. I had never been sure about the religious side but I think it was Bach who said something along the lines of “the only good thing about religion is the music”, and I quite agree. Johann Sebastian and I are at one on that.

My mother’s father, Harry Bosworth, was another influence. He had a great memory. He would know entire Shakespeare plays by heart. Years ago, when Allen Curnow was a youngish man on the ferry between Devonport and Auckland, he said he had seen the most amazing thing — a drunk man standing on top of the ferry quoting canto after canto of Don Juan — that was Harry Bosworth. Some years ago a film was made about me called The Purple Balloon, and my poem, Purple Balloon, is about Harry Bosworth. It’s got lines in it like:

When Gangrene set in

my grandfather’s feet on a rack,

laid in the hospital bed,

he watched them slowly turn black…

And on it goes.

There are poets that became huge influences on me. Like Alistair Te Ariki Campbell and James K. Baxter, who wrote the famous letter to me… it starts off:

Dear Sam, I thank you for your letter

And for the poem too, much better

To look at than the dreary words

I day by day excrete like turds

To help to Catholic bourgeoisie

To bear their own insanity;

But the most beautiful verse I was trying to get to (that’s another thing, I’m not very good at quoting verses from a poem, I have to remember the whole thing):

Dear Sam, this day as I came down

The steps that take me into town,

Rehearsing in my head these rhymes

That hold a mirror to the times,

A perfect omen crossed my track,

Pugnacious, paranoid and sly,

A tomcat with a boxer’s eye

Dripping a gum of yellow pus;

I thought that he resembled us

Who may write poems well, with luck,

About the dolls we do not fuck,

And hear the dark creek water flow

From a rock gate we do not know,

Till we ourselves become that breach

And silence is our only speech.

As a 22-year-old I received that in the mail. What a poet. What a poem. It’s quite funny, I heard somewhere that it’s been published in a big smart anthology somewhere. When Baxter wrote that, it was banned. The magazines that had published it had to destroy all copies. It’s since been published by Oxford University Press.

My mum loved a poem by E.E. Cummings called No Time Ago. One day, one of the Sisters of Mercy at the convent said to my Standard 2 class, ‘Does anyone know a poem by heart?’ So I put up my hand and I said this poem, which is a beautiful 12-liner. I don’t know where it came from but I loved it then and I love it now, it goes:

no time ago

or else a life

walking in the dark

i met christ

jesus)my heart

flopped over

and lay still

while he passed(as

close as i’m to you

yes closer

made of nothing

except loneliness.

There’s a whole chapter in a psychology book dedicated to my memory. It was written by a Professor of Psychology at Auckland University. According to that, I do know a few thousand poems.

The reason I can remember so many poems is just because I can’t forget them. I don’t really know where some of them came from and what often happens is that I don’t have a bloody clue who wrote something. I’m not really interested in poets or poetry when it all comes down to it. But I love great ones. That’s the guts of it. The ones that won’t leave me. A good poem can keep me awake all night.

Some of the poems in my head I’ve never seen written down. A friend of mine Paul Firth recently died and years ago, when his older brother Mark died, their father Clifton wrote this poem about him, and I remember when I was about 15 or so Clifton saying this:

There is no question that a star was born

a supernova flared and died

as supernovae do from time to time

yet what is this conflagration but a fission

confusion of atoms at a critical moment

nothing, nothing, nothing at all

but surely it’s enough

that now and again

a supernova flares

and a star is born.

And I had not until recently, when a friend of the family came across a copy, ever seen it written down. But I’ve known that poem, I’ve had it in my head, for 60 years.

I came across a piece the other day by a North American poet (he shot himself I think, most good poets do) Theodore Roethke, Wish for A Young Wife… this is how it goes:

My lizard, my lively writher,

May your limbs never wither,

May the eyes in your face

Survive the green ice

Of envy’s mean gaze;

May you live out your life

Without hate, without grief,

May your hair ever blaze,

In the sun, in the sun,

When I am undone,

When I am no one.

That could change your life, that poem. You might go home to your husband and say, “sorry mate, I’m off”.

I think of the poem not as written down, that’s just the score. And you can get to the poem by way of the score. But I hear poems. I know the voice of the poem. If a new poem is coming along, it’s like a pregnancy, different things happen at different times. For me, it doesn’t happen the same way every time by any means but a poem starts with a sound. It’s almost like I’ve recognised a voice from somewhere. Sometimes the poems land on the roof and I’m not sure whether it’s a possum or a poem! Something thumping across the corrugated iron on top of my house, and I think, what is that?

I’ve worked out (it’s just a theory of mine) that I’ve got five voices. Two of them are female and the other three are male. And if I wanted to, I could divide my poems up into those five voices as far as where they’ve come from. There’s a line of Ezra Pound’s (a wild old bugger — he was a contemporary and good friend of T.S. Eliot’s, who dedicated The Waste Land to him — ‘to Ezra Pound, the greater master’) that ends up talking about the five voices, and this is what he says:

Oh world my poems are written for five people

Oh world I pity you, you do not know these five people.

Isn’t that great? Long before I would come to know those lines I worked out that I basically had five lyrical voices in my heart and head.

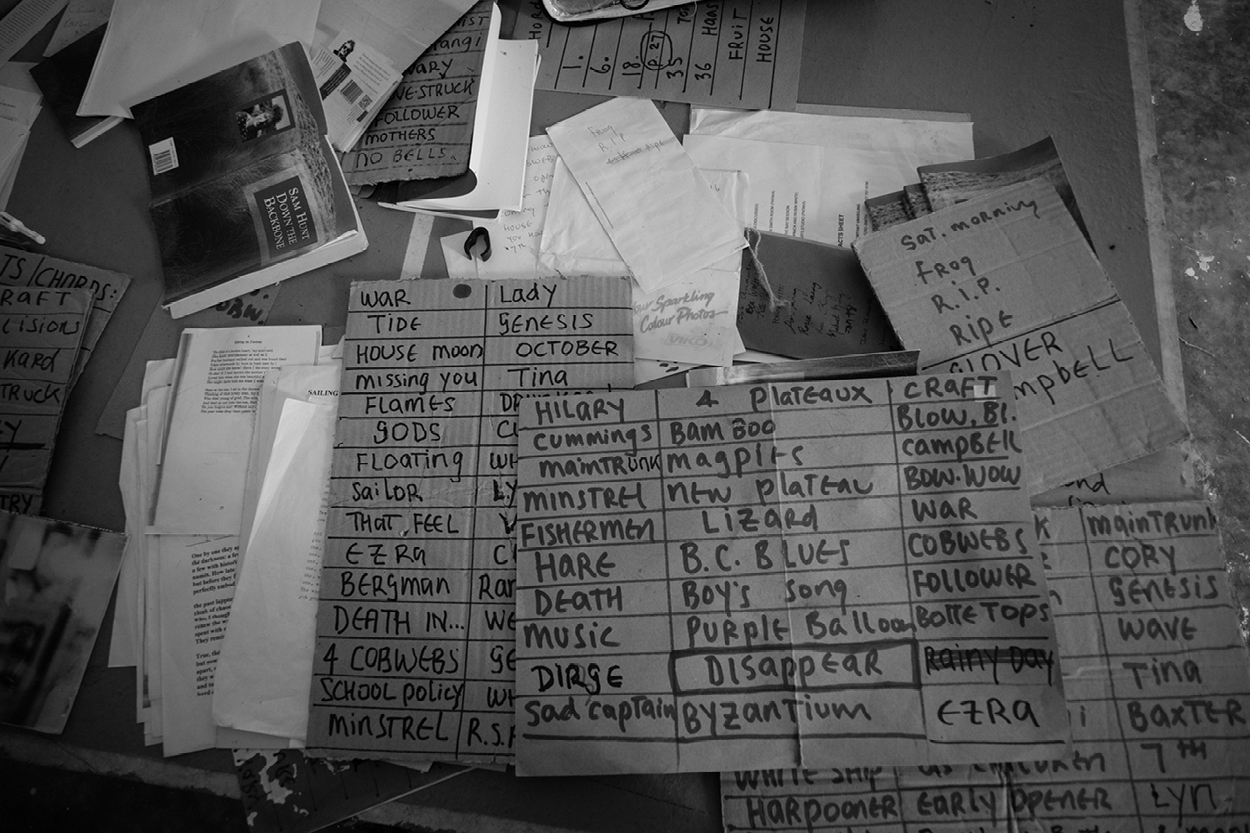

Sometimes I can make the mistake of trying to scribble a poem down too quickly in my Warwick 1B8 exercise book. But then again, if I don’t scribble something down, particularly if I wake up in the night with a line or a phrase or a word, it will be gone in the morning. So that part I recognise. But equally I recognise going the other way. It can’t be rushed. It’s a strange process and I still find myself astonished by it. It must be like the people who see birth all the time, like midwives. Most of them would agree with Ted Hughes in a poem he wrote about a birth, and in the last line, it’s a wonderful, throwaway line, he says:

Just another ten-toed, ten-fingered miracle.

The empty page is a good workbench. But I’m listening more than writing. For me it’s a sound process, which is probably part of the reason why I have often ended up working with musicians. People like Barry Saunders and David Kilgour and other people.

I didn’t have to go to a vocational guidance person to ask what I wanted to do. If somebody had stopped me in the street when I was young and said, ‘well, what are you going to do with your life?’ I don’t know, I’d have probably said I was going to go to jail or something. Do a life sentence and get it over with. I didn’t really know what I was going to do but I knew that poems were going to be at the heart of it.

When I was quite young, everyone was taking what they used to call OEs (overseas experiences) and honestly, what wankers. They came back more boring than they were before they left. And around about the same time I was discovering poets like William Blake with his lines like, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’. You don’t have to travel all around the world. I mean it’s wonderful if it helps you make something of it all, but so many people just take selfies. That happened to me recently, someone tried to take a selfie with me and I just grabbed the camera and threw it on the ground. What an insult to humanity that is?!

I hate the word career. Career is a six-letter word starting with ‘C’ like cancer. I never had a career, and I never want a career.

Experiences had more to do with my poetry than any sort of marks I got for School Certificate. I remember once, my father and I were going to see French cellist Pierre Fournier at the Auckland Town Hall (who was playing, among other things, the Dvorak cello concerto which I fell in love with that night and love to this day) and I discovered a passage from my father’s chambers on Queen Street directly to the Auckland Town Hall backstage, and I ended up in the number one backstage room where Pierre Fournier was tuning up his cello for the show.

Later that night we were walking down Queen Street to catch the ferry, and an old friend of my father’s, Lewis Eady, was closing up his music shop, but he let us go in to see if he had a copy of the Dvorak cello concerto, which we found on double vinyl. We went home and stayed up all night playing the vinyl over and over. I’d describe those kinds of moments as spiritual experiences. They’re certainly the ones that

have stayed close to my heart and consciousness, and subconsciousness.

I was very fortunate to be able to earn a living on the road. Often I’d do shows, one of my regular ones was the Gluepot in Auckland, and I’d do a one-man show where I’d get around 1000 people which was the maximum upstairs there, and it would be $10 a head. The pub would take the bar and we’d take the door. And so driving home the next day, or the day after, or the day after, I’d maybe have made, over a couple of nights, around $20,000 in cash. In the end I did get caught by the tax department. I was living outside the law. But what did Bob Dylan say? “To live outside the law, you must be honest”.

I retired on my birthday, on the 4th of July, five years ago. I do miss performing but I don’t miss the in-between bits of getting there and getting home. I miss the energy of doing shows and, although I don’t want to get sentimental about audiences, I’ve had some bloody lovely audiences. If I didn’t do a good job I didn’t expect a good reaction from the audience, and there were times that I bombed out (drunk and stoned and a long way from home) but that didn’t happen very often. And for all the times when the magic was taking place which involved not just me but every member of that audience, the relationship was almost electric. I miss that.

Now that I’ve stopped performing I’ll go downstairs in the house where I’ve got my own PA system and I turn the microphone on and I speak my poems into that. I don’t know what the cattle and the sheep think about hearing my voice booming out in the paddocks but the microphone gives me just a bit more objectivity. Again, it comes back to listening. When you go and do a show you’re putting your voice out there and it gives you that distance. I think, I wonder what this poem’s like and I wonder what it sounds like, and it’s different from sitting here and reading what I’ve scribbled down in my 1B8 Warwick. I wonder who Warwick was? I think I’d like to have met him.

Some poems are stillborn, or die young. And there are many more that maybe should have. But there are certain poems that I feel blessed to have written. There’s been a guiding hand there somewhere, or an ear that has listened and has taken it in. And it still amazes me. The poem that my mother always said meant a lot to her was one of mine called Wave Song. It’s sort of a carnal poem, a lot of them are anyway. But that makes it special.

I hope I’m not being curmudgeonly when I say that some of the biggest threats to poetry come from the writing schools. I know some of them have produced great stuff but there is great stuff that I believe would have happened anyway. Trying to learn poetry is a bit like learning how to dream. “And professor, what do I do when I close my eyes?” There are a lot of so-called poets who are being published who really haven’t done a hell of a lot more than go to a computer and start playing around with rhymes and things, and I’m thinking well, where is it coming from? I don’t need to know what a poem is about per se, I’ve never had that urge. But I want to feel that it’s going somewhere.

There’s a lot of talent among young people, but if I look for what’s happening in poetry now, I’m more inclined to listen to people like Benee and other ones like her. They’re the poets as far as I’m concerned because they’re doing it and they’re not bullshitting. There’s a lot of bullshit out there.

I love my home in the Kaipara. I live in a treehouse. I love this place. When I retired I couldn’t have been happier. And often, apart from when I go out with a couple of friends and get lost on the back roads (there are some beautiful backroads up here and sometimes there’s a pub at the end of them too) I don’t really see too many people. A lot of people like to visit people… they’re forever visiting… and I can’t work it out why anyone would visit somebody. I like the sign that apparently Bob Dylan has on his property in California that reads: ‘If you haven’t rung, you’re trespassing.’

When my youngest son Alf turned 11, I wrote 11 runes for him, and one of the little four-liners goes:

Alive Alf to live

clear of any city

live as we do

five gunshots from humanity.

And that’s where we live, five gunshots from humanity.

Alf recently gave me, for a present, six months of Spotify, which was very sweet of him except that I discovered the first six months were free anyway. I rang him and we laughed. He’s good. I thought, what a beautiful gift for a son to give his father and then I realised that it was all for free! Well, so is love, so is love.

You’ve got to fight for the ability to be still and sit in one place and listen. People will trespass on that territory easily and that’s why I do live five gunshots from humanity and not just physically and geographically but mentally. I’m not saying that I’m better than anyone, I’m just saying that I’m on my own. Jim Baxter, when he was 17 years old, wrote in High Country Weather:

Alone we are born

and die alone

Yet see the red-gold cirrus

over snow-mountain shine.

Upon the upland road

Ride easy, stranger

Surrender to the sky

Your heart of anger.

Poems are always there if you listen long enough. I had to renew my licence the other day and I overheard a phrase at the AA in Dargaville, I won’t repeat it now because I want to keep it echoing in my head, but it started me on something new. I think it was James K. Baxter who said in a poem dedicated to Maurice Shadbolt in the Pig Island Letters… ‘Whoever can listen long enough will write again.’

I’ve never worried about the dryness of the mind. At one stage I didn’t write a poem for quite a few years because I was just taken up doing other things and I wasn’t able to take the time to listen long enough… and then one day they all returned.

I stuttered quite badly from my adolescence, something I developed in puberty. And then in my later teens and early 20s I found myself out doing shows (as I did for the next 50 years), and the stutter went away completely. But in the five years that I’ve been retired from performing, I’m stuttering again and I don’t mind it. I think it had been outrun by the performances where I couldn’t stutter. And now it’s back.

I’m sort of working on a new collection. I recently wrote a poem called Mum and Mary about my mum, Betty and Mary, Mother of Jesus, out sharing a joint. It will be in this new book which I was going to call Last Poems but my publisher asked what would happen if I decided to write a few more?

I enjoy life but I’m looking forward to death. I’m three-quarters of a century now and it’s all happened really fast. I’m looking forward to having a look around the corner. ‘Hey around the corner, behind the bush, looking for Henry Lee’ (line from a 1955 song by The Weavers). That’s where I’ll be.

I don’t want to be remembered for anything. I was recently, very kindly offered an award and I just had to turn it down because it didn’t represent anything that I was about. It was a corporate thing. And they wanted to make me their poet. And I thought, if I get short of money I can stop in at a pub and play somebody on the pool table for $1000 and then move on to more dangerous places.

There’s no one really that I’ve ever fantasised about conversing with. Sitting down and talking to you is what it’s all about as far as I’m concerned. There’s a beautiful line in one of Bob Dylan’s many great songs where he says:

I have dined with kings

I’ve been offered wings

And I’ve never been too impressed.

I wonder if someone these days would be able to have a similar run to me. I hope that they would be able to, but looking back on it, it’s got to be in your blood. It’s not something you can pick out of a line-up of vocations or a booklet of possible professions. It must be very hard now. I’m recently 75 but I would find it very very tough being a 15-year-old now. It’s all so confusing.

I’m not a man for giving advice because all the advice I’ve given myself has got me into ditches. But again, I quote Bob Dylan, with the title of one of his well-known songs, ‘I Believe In You’. Believe in yourself. I know that you can’t just turn on a button and believe in yourself but make sure you get the poems down that will make you personally believe in yourself. If you’re listening to the voice, or voices and if you can tune in to your own one as it’s transmitting stuff from your conscious mind by way of your subconscious… if it’s working, it’s like love. It’s wonderful.