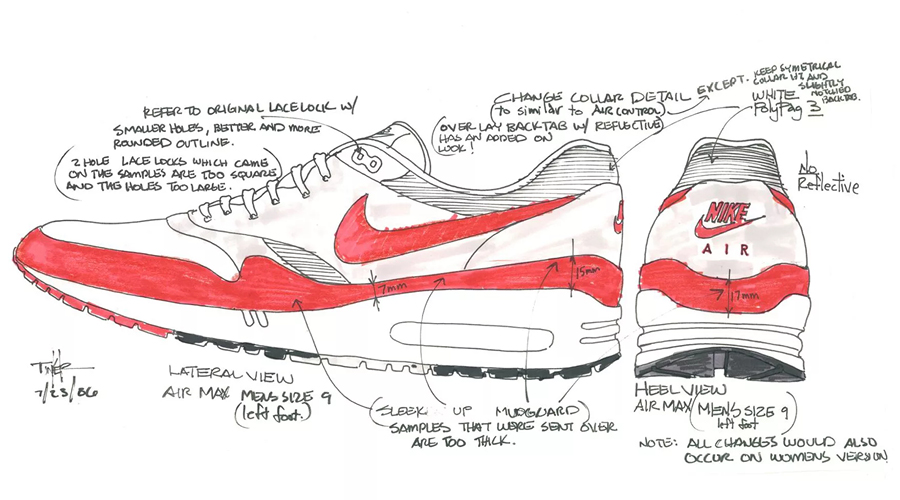

As far as sneakers go, there aren’t many as highly regarded or universally loved as Nike’s Air Max 1. It is arguably the most famous sneaker in the world. So when Nike decided, in 2017, to mark the iconic style’s 30th anniversary by reimagining the silhouette so that it recaptured the same magic as its Tinker Hatfield-designed original, it was a significant moment for both the brand and its community of followers. It was also something that Lee Gibson, one of the lead footwear designers at Nike Sportswear and the person tasked with leading the redesign (also, incidentally, a Kiwi) counts among his proudest moments. “I worked for about a year with engineers, pattern makers, other footwear designers and all these material experts to try and get us back to what the original shoe was like,” he tells me, “and seeing the shoe finally come out, and seeing people’s reactions to it felt like such an achievement.”

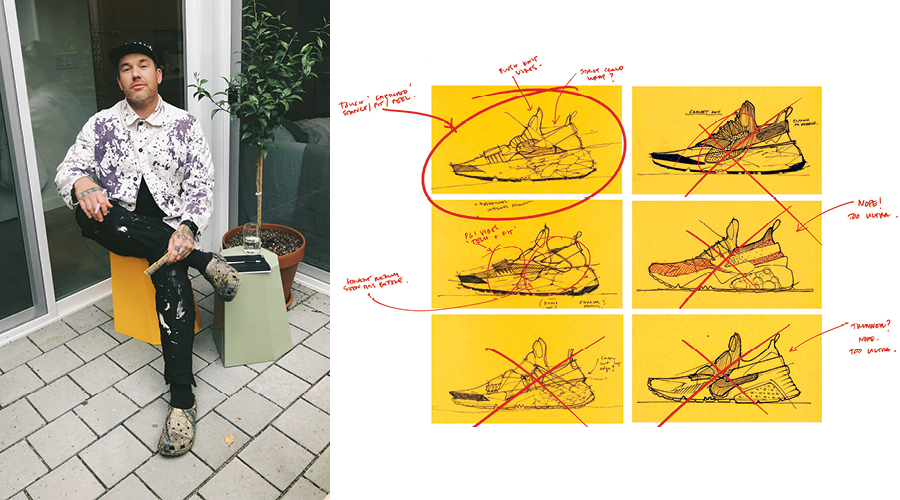

That Gibson had the wherewithal to tackle something as zeitgeist-y, as recognisable and as treasured as the Air Max 1, speaks to his character. Despite holding what is acknowledged as one of the most coveted job titles in the landscape of footwear design, Gibson doesn’t seem the type to get caught up in semantics. His success seems to have grown from an insatiable appetite for learning, and a refusal to be confined to any kind of creative box, which has seen him embody the idea of a ‘multi-hyphenate designer’ in the truest sense of that often-overused moniker. “In the early 2000s there was this push towards extreme specialisation,” he tells me, speaking about the creative industries in which he trained and now works, “but I was always on the other side of that because I wanted to mix it up, to be able to change things around and not always feel like I had to design the same thing.” He laughs, “what’s that saying… Jack of all trades, master of none?”

Sign up to our free EDM subscription today.

Gibson isn’t being glib. Nor is he simply perpetuating that Kiwi stereotype of downplaying success. His ability to work across various design disciplines has seen him undertake creative projects in a number of fields and seems to be one of the driving reasons behind his success.

Growing up in Bennydale, a small town in King Country, Gibson explains how it wasn’t until he started at Wellington’s Victoria University (studying architecture) that he really figured out what he wanted to do, and even then, it’s an idea that has remained fluid and dynamic to this day. “I was always interested in drawing and making,” he explains, “and I had some advice from a neighbour that if I wanted to get into a creative field, architecture was a good place to start.”

At university, Gibson was exposed to other creative disciplines like industrial design, which saw his architectural work veer off the traditional path. “The architecture I was immersed in at uni was focused mostly around the conceptual, the theoretical,” he says, “but I saw industrial designers who were actually making products that people could use, so I started using the same kinds of design processes to build my architectural models and I became really interested in the tension and crossover between the two areas.”

This idea of deviating from the designated path seems typical of Gibson’s education and career. His wide-reaching interests and abilities outside the traditional bounds of architecture led to him seeking work in adjacent fields, and after a stint as a lecturer at his alma mater, a desire to further his own education took him to New York’s prestigious Parsons School of Design to undertake a Masters in Fine Arts and Interior Design. It was the experiences he gained in New York — a mixture of unpaid internships and unconventional jobs for cutting-edge designers — that Gibson credits as having piqued the interest of the decision-makers at Nike five years ago, who he tells me were, at the time, looking for people that could deliver a different point of view. “They [Nike] were really interested in my eclectic background and experience,” Gibson tells me, “and at that point, I really felt like I could have been put into any scenario and apply what I’d learnt to any kind of design.”

Confirming something I had already suspected, Gibson explained how the impressive rise of creatives like Virgil Abloh had really paved the way for a new breed of designer — one who didn’t necessarily have to excel in one area or monopolise a niche to be successful. Speaking to Nike’s collaboration with Abloh a few years ago, Gibson explains that he saw a big shift in the industry, especially for people like himself, saying, “people seemed to understand that yeah, I might not be a trained footwear designer, but that maybe I could come in and that my point of view would be valid… and I backed myself.”

The footwear industry is an undeniably saturated space. So it’s no wonder that when it came to someone like Gibson, who represented a departure from the norm, a company like Nike saw value in his potential. And while the designer acknowledges that it took a bit of risk on Nike’s part to hire him, his eagerness to learn as much as he could (call it a classic case of that Kiwi, roll-up-your-sleeves mentality) quickly mitigated any liability. “I have a drive and a passion for learning and for trying things I haven’t done before, so when anyone wanted help, I would put my hand up,” Gibson tells me, “I worked with engineers, I worked with developers, I worked with our research lab… and I was going home at night and doing tutorials to try and up-skill myself because I was working in such a different way from the other designers.”

The design work that Gibson now does for Nike is the result of the creative and practical agility he gained by seeking to understand every aspect of the process. Having primarily been involved in designing shoes under the Nike Sportswear umbrella, which covers day-to-day, leisure styles for the brand, Gibson reveals that he is now starting to design high-performance shoes for professional athletes. “I’m really excited about working with athletes,” he tells me, “because it’s just such a different world and I feel like I can bring something a little bit fresh.”

Citing Michael Jordan and the All Blacks as sporting entities he looked up to growing up, Gibson explains that to be able to now sit down with the likes of Lebron James and Russell Westbrook (both prominent players in the NBA) and gain insight into their personal stories and what has driven them to achieve such lofty career highs is inspiring. Recently, Gibson assisted on a

project to create a pair of pregame cleats for Odell Beckham Jr (a renowned NFL player) that flipped the script on the signature Nike Swoosh, seeing the red satin of the shoes covered in miniature versions of the iconic symbol.

But Gibson isn’t one to forget his roots, telling me in between stories about iconic shoes and renowned athletes that he still finds inspiration back home. “The work that New Zealand designers produce is truly world class,” he explains, citing students he once taught as examples, which happens to include acclaimed interior designer Rufus Knight, (someone Gibson explains as a good friend and constant source of creative influence).

Certainly not one to sing his own praises, Gibson, despite his objective success, still speaks in that slightly self-deprecating, unquestionably humble way us New Zealanders have built our reputation on. “I feel like I haven’t achieved anything yet, really,” Gibson says, continuing, “I still think my proudest moments have been working on shoes where most people don’t realise the hours of design work that have gone on behind the scenes — like with the Air Max 1,” for which the process was apparently painstaking.

For Gibson then, it seems the joy is in the act of creating. Of conceptualising, innovating and bringing to life the kinds of shoes that he was inspired by and collected when he was younger.

“Around 15 years ago, Nike designed a shoe called the Mayfly,” Gibson tells me, after I ask whether he has a favourite sneaker in his own collection, “and the cool thing about that shoe is that it was designed to only last for 100 kilometres before falling apart, then you’d send it back to Nike and they’d recycle it for you.” It was designs like the Mayfly — ones that were cutting edge, ahead of their time and seeking to shift people’s perceptions around how something was made and question the idea of purpose — that Gibson seems to have used as cornerstones for his own unique ethos and methodology.

This year, the designer worked on a project that created a number of new, concept-driven Nike Labels, seeing him and his team pull inspiration from Nike’s archives to reimagine the past with a contemporary filter. Resulting in sub-labels like the N.354, D/MS/X and THE10TH, the endeavour, in the way that it took something tried and true, something already in existence and imbued it with new meaning, felt emblematic of what Gibson himself represents — a changing of the old guard.

And with issues like sustainability, as it relates to both antiquated manufacturing processes and the environment, a ubiquitous presence in mainstream footwear (now, 75 percent of all Nike apparel and footwear contains some recycled material, and the company is working towards a goal of using 100 percent renewable energy, globally, by 2025) it’s the designers that are unafraid to embrace change, designers like Gibson, who will likely be the ones to lead the industry into the future.